Protostane and Fusidane Triterpenes: A Mini-Review

Abstract

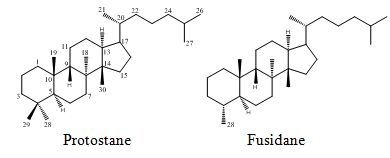

:1. Introduction

2. Protostane Triterpenes

2.1. Distribution of Protostane Triterpenes in Higher Plants

| No. | Name | M.F. | Source | Sub-group a | Bioassays conducted b | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alisol A | C30H50O5 | Alisma orientale,A. planta-aquatica | I | 5 | [3,9,10,11,12,13,14] |

| 2 | Alisol A 24-acetate | C32H52O6 | A. orientale,A. planta-aquatica | I | 7 | [3,5,9,10,11,12,15,16] |

| 3 | Alisol F | C30H48O5 | A. gramineum,A. orientale,Lobelia chinensis | I | 2 | [5,6,11,17,18,19] |

| 4 | Alisol G (25-anhydroalisol A) | C30H48O4 | A. orientale,A. planta-aquatica | I | 4 | [5,10,11,13,19] |

| 5 | 13β,17β-Epoxyalisol A | C30H50O6 | A. orientale | I | 2 | [4,5,19] |

| 6 | 11-Deoxyalisol A | C30H50O4 | A. orientale | I | - | [20] |

| 7 | 11-Deoxy-13β,17β-epoxyalisol A | C30H50O5 | A. orientale | I | - | [20] |

| 8 | 25-O-Methylalisol A | C31H52O5 | A. orientale | I | - | [20] |

| 9 | 16-Oxoalisol A | C30H48O6 | A. orientale | I | 1 | [4,20] |

| 10 | 16-Oxo-11-anhydroalisol A | C30H46O5 | A. orientale | I | - | [21] |

| 11 | 16-Oxo-23-deoxyalisol A | C30H48O5 | A. orientale | I | - | [21] |

| 12 | Alizexol A(alisol F 24-acetate) | C32H50O6 | A. orientale | I | 1 | [5,6,22] |

| 13 | Alisol H | C30H46O4 | A. orientale | I | 1 | [11,23] |

| 14 | Alismaketone B 23-acetate | C32H50O6 | A. orientale | I | - | [11] |

| 15 | 25-Anhydroalisol A 11-acetate | C32H50O5 | A. orientale | I | - | [24] |

| 16 | 25-Anhydroalisol A 24-acetate | C32H50O5 | A. orientale | I | - | [24] |

| 17 | Neoalisol | C30H46O4 | A. orientale | I | - | [24] |

| 18 | 13β,17β-Epoxyalisol A 24-acetate | C32H52O7 | A. orientale | I | - | [25] |

| 19 | Alisol O | C32H48O5 | A. orientale | I | - | [5] |

| 20 | 24-Deacetylalisol O(11-anhydroalisol F) | C30H46O4 | A. orientale | I | - | [26] |

| 21 | 25-Anhydroalisol F | C30H46O4 | A. orientale | I | - | [27] |

| 22 | 11,25-Anhydroalisol F | C30H44O3 | A. orientale | I | - | [28] |

| 23 | Alisol X | C30H46O3 | A. orientale | I | - | [29] |

| 24 | Alisol B | C30H48O4 | A. orientale | II | 8 | [9,11,12,14,15,17,30,31] |

| 25 | Alisol B 23-acetate | C32H50O5 | A. orientale,A. planta-aquatica | II | 12 | [3,5,9,11,14,15,16,17,32,33] |

| 26 | 11-Deoxyalisol C | C30H46O4 | A. gramineum,A. orientale,A. planta-aquatica | II | - | [18,23,34] |

| 27 | Alisol D(13β,17β-epoxyalisol B 23-acetate) | C32H50O6 | A. orientale,A. planta-aquatica | II | - | [21,34] |

| 28 | 16β-Hydroxyalisol B 23-acetate | C32H50O6 | A. gramineum,A. orientale,A. planta-aquatica | II | 1 | [18,20,31,35] |

| 29 | 16β-Methoxyalisol B 23-acetate | C33H52O6 | A. gramineum,A. planta-aquatica | II | - | [18,35] |

| 30 | 11-Deoxyalisol B | C30H48O3 | A. orientale | II | 2 | [11,31,36] |

| 31 | 11-Deoxyalisol B 23-acetate | C32H50O4 | A. orientale | II | - | [36] |

| 32 | Alisol C | C30H46O5 | A. orientale | II | - | [20] |

| 33 | Alisol C 23-acetate | C32H48O6 | A. orientale | II | 5 | [3,14,15,20,31,33] |

| 34 | 11-Deoxyalisol C 23-acetate | C32H48O5 | A. orientale | II | - | [20] |

| 35 | 16β,23β-Oxidoalisol B | C30H46O4 | A. gramineum,A. orientale | II | - | [18,20] |

| 36 | 13β,17β-Epoxyalisol B | C30H48O5 | A. orientale | II | - | [20] |

| 37 | 11-Deoxy-13β,17β-epoxyalisol B 23-acetate | C32H50O5 | A. orientale | II | - | [20] |

| 38 | Alismaketone A 23-acetate | C32H50O6 | A. orientale | II | 1 | [37] |

| 39 | Alisol I | C30H46O3 | A. orientale | II | 1 | [11,23] |

| 40 | Alisol J 23-acetate | C32H46O6 | A. orientale | II | - | [23] |

| 41 | Alisol K 23-acetate | C32H46O6 | A. orientale | II | 1 | [11,23] |

| 42 | Alisol L 23-acetate | C32H46O5 | A. orientale | II | 1 | [11,23] |

| 43 | Alisol M 23-acetate | C32H48O7 | A. orientale | II | 1 | [11,23] |

| 44 | Alisol N 23-acetate | C32H50O6 | A. orientale | II | 1 | [11,23] |

| 45 | Alisol Q 23-acetate | C32H48O6 | A. orientale | II | - | [38] |

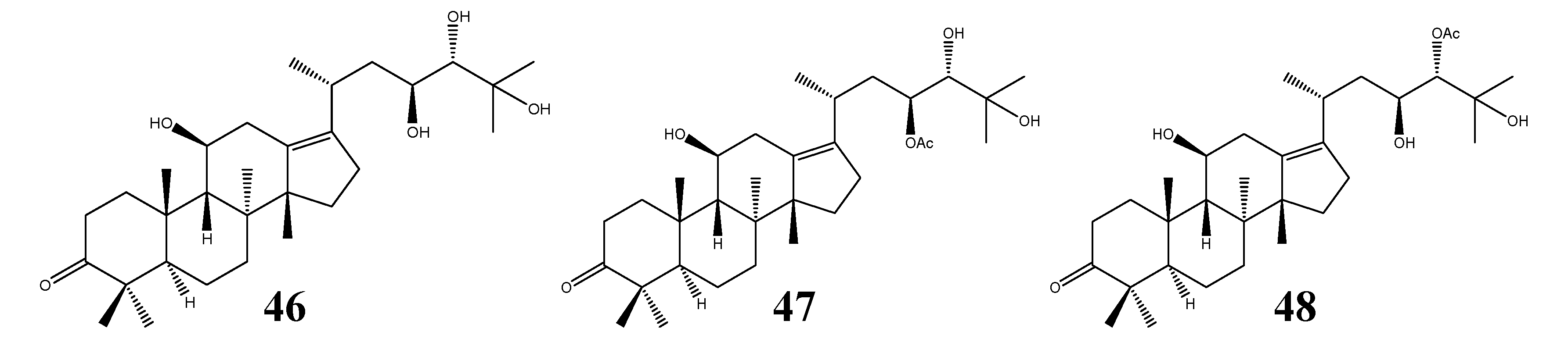

| 46 | Alisol E (epi-alisol A) | C30H50O5 | A. orientale | III | 1 | [9,11,37] |

| 47 | Alisol E 23-acetate | C32H52O6 | A. orientale | III | 1 | [11,19] |

| 48 | Alisol E 24-acetate | C32H52O6 | A. orientale | III | - | [25] |

| 49 | Alismalactone 23-acetate | C32H48O7 | A. orientale | IV | 2 | [11,37] |

| 50 | 3-Methyl alismalactone 23-acetate | C33H50O7 | A. orientale | IV | 1 | [11] |

| 51 | Alisol P | C30H48O7 | A. orientale | IV | - | [39] |

| 52 | Alismaketone C 23-acetate | C32H48O6 | A. orientale | IV | 1 | [11] |

| 53 | Alisolide | C26H36O4 | A. orientale | V | - | [39] |

| 54 | 3-Oxo-13β,23-dihydroxy-24,24-dimethyl-26,27-dinorprotost-13(17)-en-25-oic acid | C30H48O5 | A. orientale | VI | - | [39] |

| 55 | Garciosaterpene A | C32H50O4 | Garcinia speciosa | 1 | [7] | |

| 56 | Garciosaterpene B | C30H48O3 | G. speciosa | - | [7] | |

| 57 | Garciosaterpene C | C30H46O3 | G. speciosa | 1 | [7] | |

| 58 | Leucastrin A | C31H54O2 | Leucas cephalotes | - | [8] | |

| 59 | Leucastrin B | C30H52O3 | L. cephalotes | - | [8] |

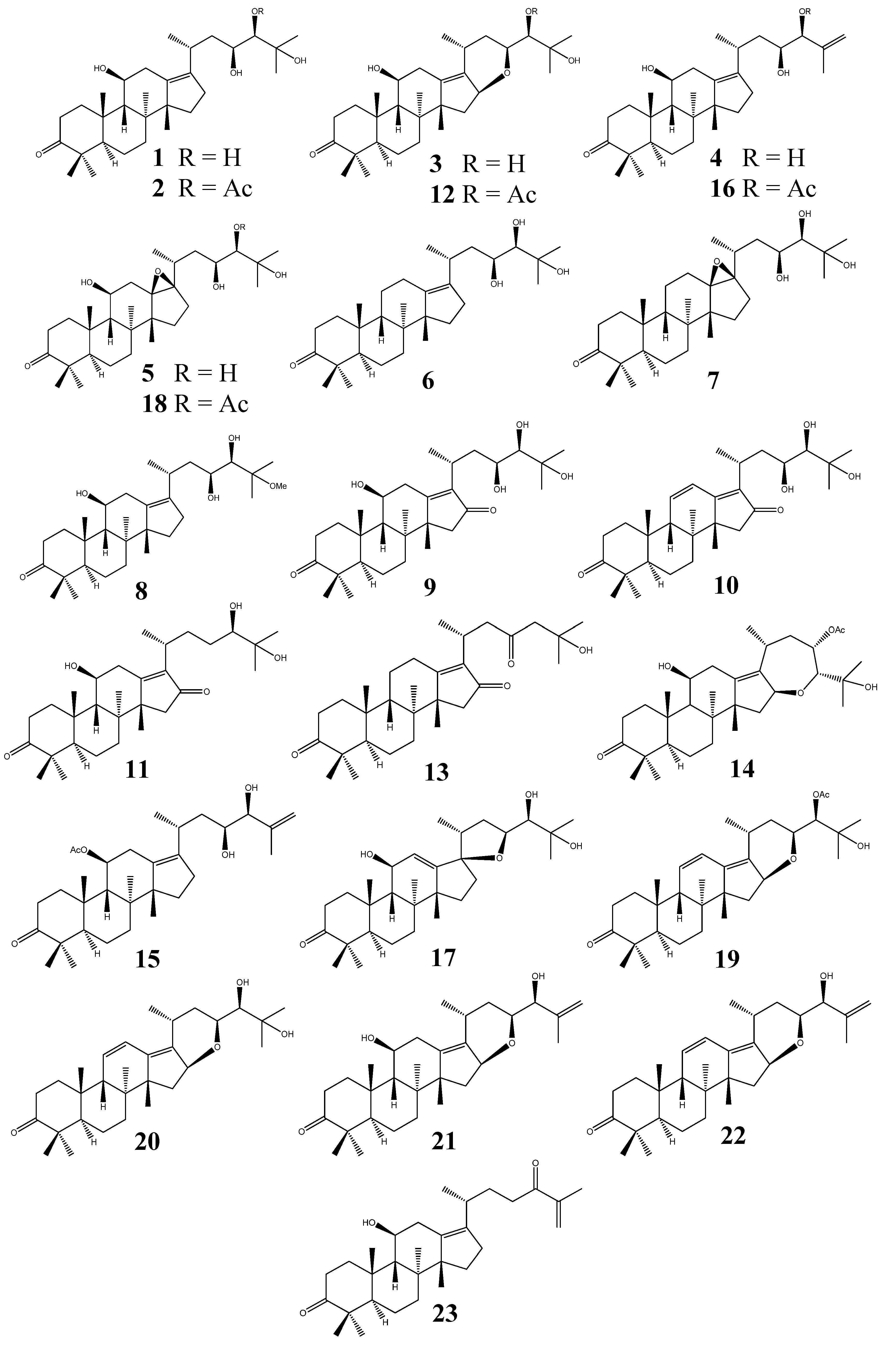

2.2. Protostane Triterpenes from Alisma

2.2.1. Characteristic Structural Features and Classification

- (I)

- Alisol A series: (20R, 23S, 24R) configuration; without a 24,25-epoxy group;

- (II)

- Alisol B series: bearing a 24,25-epoxy group;

- (III)

- Alisol E series: (20R, 23S, 24S) configuration; without a 24,25-epoxy group;

- (IV)

- Seco-PTs: 2,3-seco and 13,17-seco derivatives (the affix seco is used to denote the cleavage of a ring in a parent structure);

- (V)

- Nor-PTs: 24,25,26,27-tetra-nor-protostane (The affix nor is used to denote the elimination of one or more carbons from the parent structure);

- (VI)

- Rearranged PTs.

2.2.2. Spectral Characteristics in IR, UV, MS, and NMR

2.2.2.1. IR, UV, and MS Spectra

2.2.2.2. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectra

2.2.3. Alisol A Series

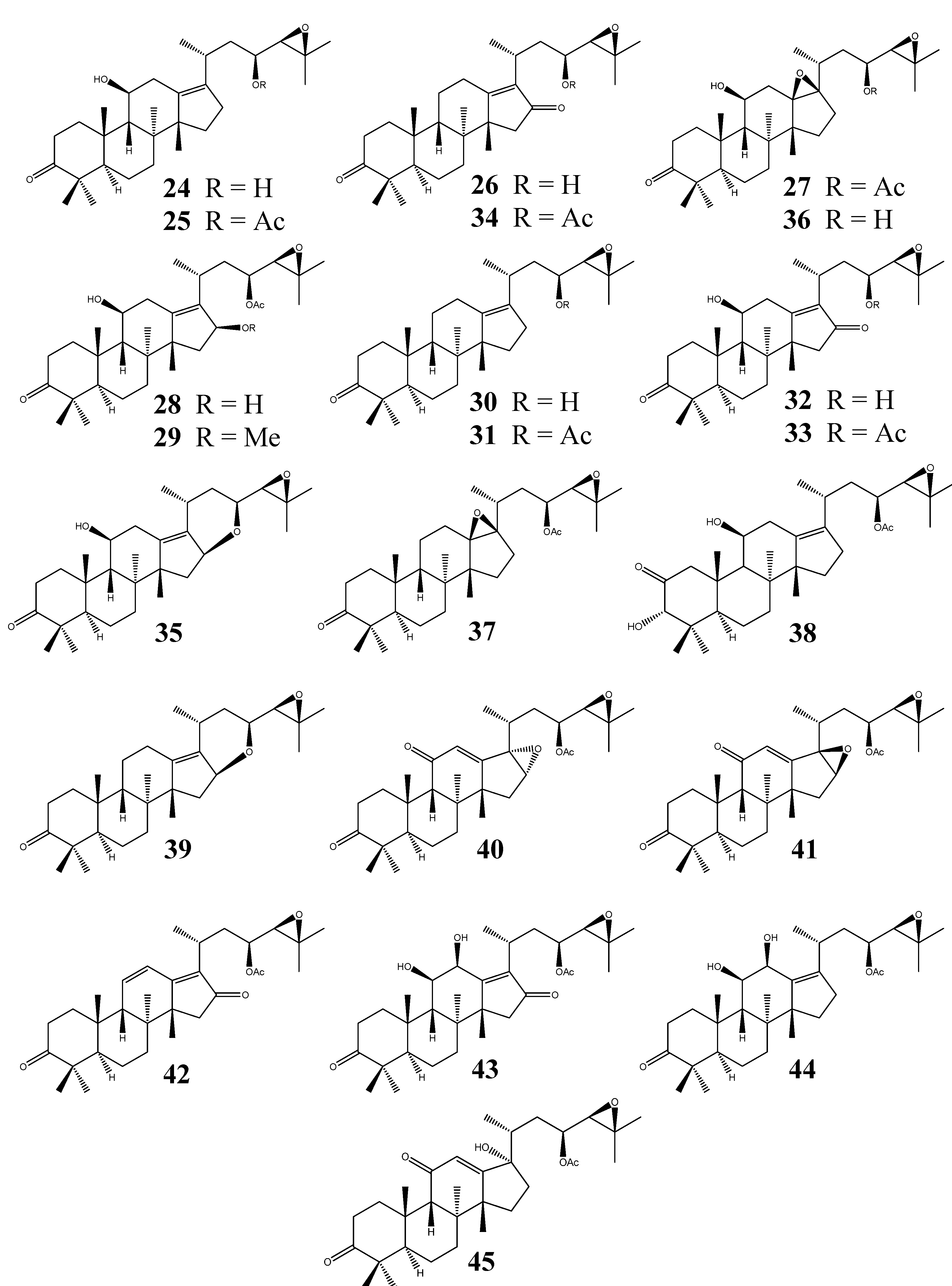

2.2.4. Alisol B Series

2.2.5. Alisol E Series

2.2.6. Seco-Protostane Triterpenes

2.2.7. Nor-Protostane Triterpenes and Rearranged Protostane Triterpenes

2.3. Protostane Triterpenes from Other Plant Species

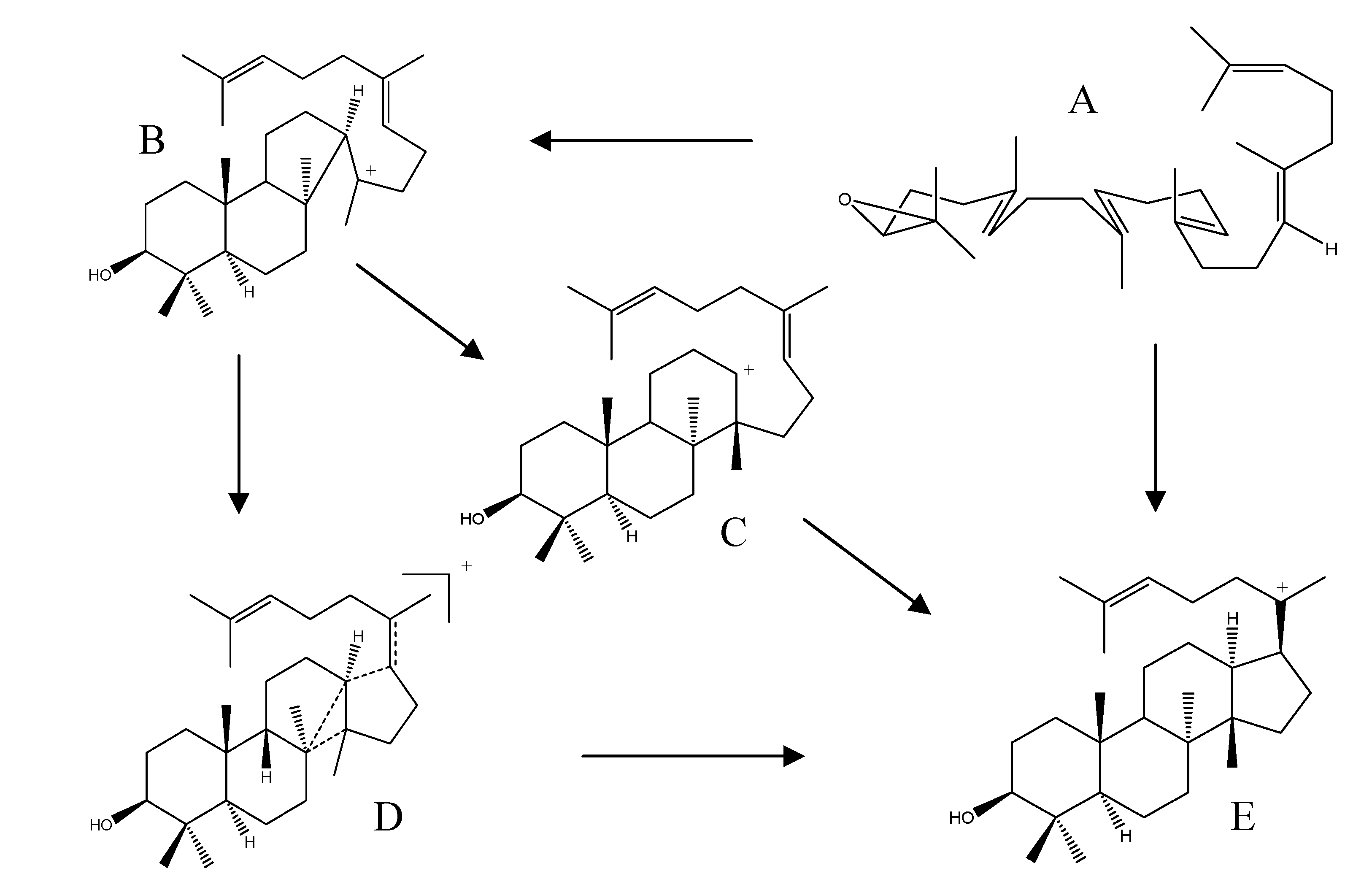

2.4. Biogenesis of Protostanes

2.5. Biological Activities of Protostane Triterpenes

2.5.1. Lipotropic and Liver-Protective Activity

2.5.3. Anti-Tumor Activity

2.5.4. Multi-Drug Resistance Reversal Activity in Cancer Therapy

2.5.5. Anti-Complement Activity

2.5.6. Other Biological Activities

3. Fusidane Triterpenes

| No. | Name | M.F. | Source | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | Fusidic acid | C31H48O6 | Acremonium fusidioides, Calcarisporium arbuscula, Cephalosporium lamellaecula, C. acremonium, Epidermophyton floccosum, Fusidium coccineum, Gabarnaudia tholispora, Mucor ramannianus, Paecilomyces fusidioides | [64,65,66,67] |

| 61 | Helvolic acid | C33H44O8 | Aspergillus fumigatus, A. sydowi, A. sp. CY725, Alternaria sp. FL25, Cephalosporium caerulens, Emericellopsis terricola, Metarhizium anisopliae, Penicilliopsis sp., Pichia guilliermondii, Sarocladium oryzae | [1,66,75,79] |

| 62 | Cephalosporin P1 | C33H50O8 | Cephalosporium acremonium, Cladosporium sp. | [66,81,84,85,86] |

| 63 | Isocephalosporin P1 | C33H50O8 | Cephalosporium acremonium | [84] |

| 64 | Monodesacetyl cephalosporin P1 | C31H48O7 | Cephalosporium acremonium | [84] |

| 65 | Viridominic acid A | C33H48O9 | Cladosporium sp. | [66,85,86] |

| 66 | Viridominic acid B | C33H48O10 | Cladosporium sp. | [66,85,86] |

| 67 | Viridominic acid C | C33H50O9 | Cladosporium sp. | [66,85,86] |

| 68 | 3-Ketofusidic acid | C31H46O6 | Epidermophyton floccosum, Fusidium coccineum | [65,67] |

| 69 | 11-Ketofusidic acid | C31H46O6 | Fusidium coccineum | [65] |

| 70 | 3-Epifusidic acid | C31H48O6 | Fusidium coccineum | [65] |

| 71 | 11-Epifusidic acid | C31H48O6 | Fusidium coccineum | [65] |

| 72 | 9,11-Anhydrofusidic acid | C31H46O5 | Fusidium coccineum | [65] |

| 73 | 9,11-Anhydro-9 α,11α-epoxyfusidic acid | C31H46O6 | Fusidium coccineum | [65] |

| 74 | 9,11-Anhydro-12-hydroxyfusidic acid | C31H46O6 | Fusidium coccineum | [65] |

| 75 | Fusilactidic acid | C31H46O7 | Fusidium coccineum | [65] |

| 76 | 3,11-Diketofusidic acid | C31H44O6 | Epidermophyton floccosum | [67] |

| 77 | 16-Deacetoxy-7 β-hydroxy fusidic acid | C29H46O5 | Acremonium crotocinigenum | [87] |

3.1. Structural Features

3.2. Fusidic Acid

3.3. Other Fusidane Triterpenes

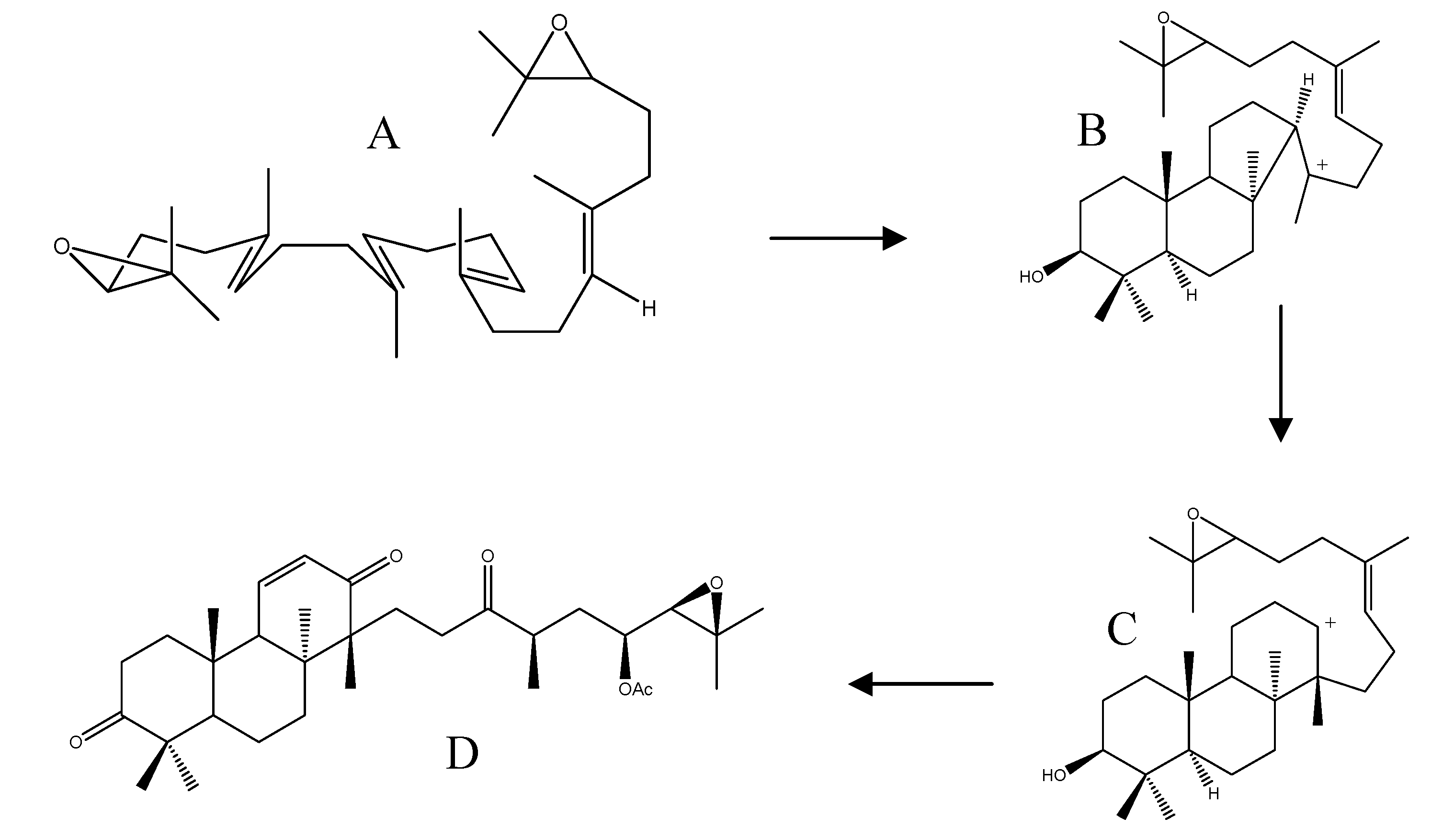

3.4. Biosynthesis of Fusidane Triterpenes

4. Conclusions and Future Prospects

Acknowledgments

References and Notes

- Hattori, T.; Igarashi, H.; Iwasaki, S.; Okuda, S. Helvolic acid and related compounds. VI. Isolation of 3β-hydroxy-4β-methylfusida-17(20)[16,21-cis],24-diene (3β-hydroxyprotosta-17(20)[16,21-cis],24-diene) and a related triterpene alcohol. Tetrahedron Lett. 1969, 10, 1023–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaad, A.S.; Singh, V.K.; Govil, J.N. Recent Progress in Medicinal Plants; Studium Press, LLC: Houston, TX, USA, 2010; Volume 28, pp. 427–445. [Google Scholar]

- Murata, T.; Imai, Y.; Hirata, T.; Miyamoto, M. Biological-active triterpenes of Alismatis rhizoma. I. Isolation of the alisols. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1970, 18, 1347–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, H.; Ogata, T.; Sato, Y. Preparation of 16-ketoalisol A, and alisol A derivatives for treatment of liver disorders. JP 04077427, 11 March 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.Y.; Zhang, X.M.; Zhang, F.X.; Liu, N.; Zhao, F.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J.J. A new triterpene and anti-hepatitis B virus active compounds from Alisma orientalis. Planta Med. 2006, 72, 951–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.B.; Kong, L.Y. Alisol F 24-acetate: (24R)-24-acetoxy-11β,25-dihydroxy-16β,23β-epoxyprotost-13(17)-en-3-one. Acta Crystallogr. E 2007, E63, o4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukachaisirikul, V.; Pailee, P.; Hiranrat, A.; Tuchinda, P.; Yoosook, C.; Kasisit, J.; Taylor, W.C.; Reutrakul, V. Anti-HIV-1 protostane triterpenes and digeranylbenzophenone from trunk bark and stems of Garcinia speciosa. Planta Med. 2003, 69, 1141–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyaichi, Y.; Segawa, A.; Tomimori, T. Studies on nepalese crude drugs. Chemical constituents of dronapuspi, the whole herb of Leucas cephalotes SPRENG. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2006, 54, 1370–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, T.; Shinohara, M.; Hirata, T.; Kamiya, K.; Nishikawa, M.; Miyamoto, M. New triterpenes of Alismaplantago-aquatica var. orientale. Tetrahedron Lett. 1968, 9, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, V.M.; Phan, V.K.; Pham, H.Y.; Tran, T.H.; Braca, A. Protostane-type triterpenes from the rhizomes of Alisma plantago-aquatica. Tap Chi Hoa Hoc 2007, 45, 120–125. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, H.; Kageura, T.; Toguchida, I.; Murakami, T.; Kishi, A.; Yoshikawa, M. Effects of sesquiterpenes and triterpenes from the rhizome of Alisma orientale on nitric oxide production in lipopolysaccharide-activated macrophages: Absolute stereostructures of alismaketones-B 23-acetate and -C 23-acetate. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999, 9, 3081–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, H.; Tomohiro, N.; Yoshikawa, M.; Kubo, M. Studies on Alismatis Rhizoma. II. Anti-complementary activities of methanol extract and terpene components from Alismatis Rhizoma (Dried rhizome of Alisma orientale). Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1998, 21, 1317–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.; Gschwind, S.; Zimmermann, S.; Kaiser, M.; Hamburger, M. Renaissance remedies: Antiplasmodial protostane triterpenoids from Alisma plantago-aquatica L. (Alismataceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 135, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Kang, S.W.; Kim, Y.; Shin, M.; Hong, M.; Seo, E.K.; Kim, S.H.; Nah, S.Y.; Bae, H. Effects of protostane-type triterpenoids on the 5-HT3A receptor-mediated ion current in Xenopus oocytes. Brain Res. 2010, 1331, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kho, Y.; Min, B.; Kim, J.; Na, M.; Kang, S.; Maeng, H.; Bae, K. Cytotoxic triterpenoids from Alismatis Rhizoma. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2001, 24, 524–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikino, H.; Iwakawa, T.; Oshima, Y.; Nishikawa, K.; Murata, T. Efficacy of oriental drugs. 34. Diuretic principles of Alisma plantago-aquatica var. orientale rhizomes. Shoyakugaku Zasshi 1982, 36, 150–153. [Google Scholar]

- Murata, T.; Shinohara, M.; Hirata, T.; Miyamoto, M. Structures of alisol B and alisol A monacetate-occurrence of a facile acyl migration. Tetrahedron Lett. 1968, 9, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wo, L.; Luo, G.; Wang, B.; Zhu, W. Studies on triterpenes chemical constituents in rhizome of Alisma gramineum. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi 2005, 30, 1263–1265. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Hatakeyama, S.; Tanaka, N.; Fukuda, Y.; Yamahara, J.; Murakami, N. Crude drugs from aquatic plants. I. On the constituents of Alismatis Rhizoma. (1). Absolute stereostructures of alisols E 23-acetate, F, and G, three new protostane-type triterpenes from Chinese Alismatis Rhizoma. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1993, 41, 1948–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, Y.; Satoh, Y.; Katsumata, M.; Tsujiyama, K.; Ida, Y.; Shoji, J. Terpenoids of Alisma orientale rhizomes and the crude drug Alismatis rhizoma. Phytochemistry 1994, 36, 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, T.; Tomita, M.; Takigawa, M.; Iwasaki, H.; Hirukawa, T.; Yamahara, J. Inhibitory effects and active constituents of Alisma rhizomes on vascular contraction induced by high concentration of KCl. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1994, 67, 1394–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Pen, X.; Zhang, R.Y. Alizexol A, a novel protostane type of triterpene from Alisma orientalis (SAM) Juzep. Chin. Chem. Lett. 1995, 6, 675–678. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Tomohiro, N.; Murakami, T.; Ikebata, A.; Matsuda, H.; Matsuda, H.; Kubo, M. Studies on alismatis rhizoma. III. Stereostructures of new protostane-type triterpenes, alisols H, I, J-23-acetate, K-23-acetate, L-23-acetate, M-23-acetate, and N-23-acetate, from the dried rhizome of Alisma orientale. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1999, 47, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.P.; Zhu, G.Y.; Lou, F.C. Two novel terpenoids from Alisma orientalis Juzep. Tianran Chanwu Yanjiu Yu Kaifa 2002, 14, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, G.P.; Zhu, G.Y.; Lou, F.C. Terpenoids from Alisma orientalis Juzep. Tianran Chanwu Yanjiu Yu Kaifa 2002, 14, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, A.C.; Zhang, C.F.; Zhang, M. A new protostane triterpenoid from the rhizome of Alisma orientale. Zhongguo Tianran Yaowu 2008, 6, 109–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.Y.; Guo, Y.Q.; Gao, W.Y.; Zhang, T.J.; Chen, H.X. Two new triterpenes from the rhizomes of Alisma orientalis. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2008, 10, 487–490. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.Y.; Guo, Y.Q.; Gao, W.Y.; Chen, H.X.; Zhang, T.J. A new triterpenoid from Alisma orientalis. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2008, 19, 438–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Zhang, H.; Xie, X. A new triterpene in rhizome of Alisma orientale. Zhongcaoyao 2012, 43, 841–843. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, H.S.; Chung, S.H.; Kim, Y.S. Effect of alisols isolated from Alisma orientale Jazep. against several agonists in isolated rat ileum. Soul Taehakkyo Saengyak Yonguso Opjukjip 1981, 20, 79–81. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, S.; Yamaguchi, T.; Naito, T.; Hashimoto, K. Alisol B analogs for restoration of choline acetyltransferase. JP 07173188, 11 July 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.T.; Huang, D.M.; Chueh, S.C.; Teng, C.M.; Guh, J.H. Alisol B acetate, a triterpene from Alismatis rhizoma, induces Bax nuclear translocation and apoptosis in human hormone-resistant prostate cancer PC-3 cell. Cancer Lett. 2006, 231, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, I.M.; Kim, Y.S.; Yun, H.S.; Kim, S.O. Liver-protective activities of alisol compounds against carbon tetrachloride intoxication. Saengyak Hakhoe Chi (Hanguk Saengyak Hakhoe) 1982, 13, 112–115. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, Y.; Geng, P.; Wang, R.; Yamada, T.; Nakagawa, K. 11-Deoxyalisol C and alisol D: New protostane-type triterpenoids from Alisma plantago-aquatica. Planta Med. 1988, 54, 445–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, P.; Fukuyama, Y.; Yamada, T.; Rei, W.; Jinxian, B.; Nakagawa, K. Triterpenoids from the rhizome of Alisma plantago-aquatica. Phytochemistry 1988, 27, 1161–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Hatakeyama, S.; Tanaka, N.; Matsuoka, T.; Yamahara, J.; Murakami, N. Crude drugs from aquatic plants. II. On the constituents of the rhizome of Alisma orientale Juzep. originating from Japan, Taiwan, and China. Absolute stereostructures of 11-deoxyalisols B and B 23-acetate. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1993, 41, 2109–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Murakami, T.; Ikebata, A.; Ishikado, A.; Murakami, N.; Yamahara, J.; Matsuda, H. Absolute stereostructures of alismalactone 23-acetate and alismaketone-a 23-acetate, new seco-protostane and protostane-type triterpenes with vasorelaxant effects from Chinese Alismatis Rhizoma. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1997, 45, 756–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.-G.; Jin, Q.; Ryun, K.A.; Choi, H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, D.G.; Woo, E.-R. A new triterpenoid from Alisma orientale and their antibacterial effect. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2012, 35, 1919–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Xu, L.J.; Che, C.T. Alisolide, alisols O and P from the rhizome of Alisma orientale. Phytochemistry 2007, 69, 527–532. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Li, S.L.; Zhou, Y.; Song, J.Z.; Zheng, Y.F.; Peng, G.P.; Xu, H.X. Characterization of protostane triterpenoids in Alisma orientalis by ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 24, 1514–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, K.; Murata, T.; Nishikawa, M. Biological-active triterpenes of Alismatis rhizoma. III. X-ray crystallography of alisol A (23, 24)-acetonide 11-monobromoacetate. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1970, 18, 1362–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.P.; Lou, F.C. Chemical studies on Alisma orientalis Juzep. Tianran Chanwu Yanjiu Yu Kaifa 2001, 13, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, N.; Yagi, N.; Murakami, T.; Yoshikawa, M. Electrochemical transformation of protostane type triterpenes. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1996, 44, 633–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.P.; Sun, C.R.; Li, X.Y.; Sun, H.X.; Pan, Y.J. Alisol B monoacetate from the rhizome of Alisma orientale. Acta Crystallogr. E 2003, E59, o1858–o1859. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, K.; Ida, Y.; Nakajima, Y.; Satoh, Y.; Shoji, J. Absolute stereostructure of 13,17-epoxyalisol B 23-acetate isolated from Alisma orientale. Acta Crystallogr. C 1994, C50, 736–738. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.M.; Kim, J.H.; Zhang, Y.; An, R.B.; Min, B.S.; Joung, H.; Lee, H.K. Anti-complementary activity of protostane-type triterpenes from Alismatis rhizoma. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2003, 26, 463–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Fazio, G.C.; Matsuda, S.P.T. On the origins of triterpenoid skeletal diversity. Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 261–291. [Google Scholar]

- Corey, E.J.; Virgil, S.C.; Cheng, H.; Baker, C.H.; Matsuda, S.P.T.; Singh, V.; Sarshar, S. New insights regarding the cyclization pathway for sterol biosynthesis from (S)-2,3-oxidosqualene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 11819–11820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corey, E.J.; Cheng, H. Conversion of a C20 2,3-oxidosqualene analog to tricyclic structures with a five-membered C-ring by lanosterol synthase. Further evidence for a C-ring expansion step in sterol biosynthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 2709–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, B.A., Jr. Concomitant C-ring expansion and D-ring formation in lanosterol biosynthesis from squalene without violation of Markovnikov’s Rule. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 10286–10287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, B.A., Jr. Formation of the C ring in the lanosterol biosynthesis from squalene. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, I. Enzymatic synthesis of cyclic triterpenes. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007, 24, 1311–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.F.; Zhu, Y.L.; Peng, G.P. Transformation of alisol B 23-acetate in processing of Alisma orientalis. Zhongcaoyao 2006, 37, 1479–1482. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Yamaguchi, S.; Chatani, N.; Nishino, Y.; Matsuoka, T.; Yamahara, J.; Murakami, N.; Matsuda, H.; Kubo, M. Crude drugs from aquatic plants. III. Quantitative analysis of triterpene constituents in alismatis rhizoma by means of high-performance liquid chromatography on the chemical change of the constituents during alismatis rhizoma processing. Yakugaku Zasshi 1994, 114, 241–247. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A.J. 24(S),25-Epoxycholesterol: A messenger for cholesterol homeostasis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009, 41, 744–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, T.A. The squalene dioxide pathway of steroid biosynthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 1994, 27, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Jiang, Z.Y.; Luo, J.; Cheng, P.; Ma, Y.B.; Zhang, X.M.; Zhang, F.X.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J.J. Anti-HBV agents. Part 1: Synthesis of alisol A derivatives: A new class of hepatitis B virus inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 4647–4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Jiang, Z.Y.; Luo, J.; Liu, J.F.; Ma, Y.B.; Guo, R.H.; Zhang, X.M.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J.J. Anti-HBV agents. Part 2: Synthesis and in vitro anti-hepatitis B virus activities of alisol A derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 2148–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Jiang, Z.Y.; Luo, J.; Ma, Y.B.; Liu, J.F.; Guo, R.H.; Zhang, X.M.; Zhou, J.; Niu, W.; Du, F.F.; et al. Anti-HBV agents. Part 3: Preliminary structure-activity relationships of tetra-acylalisol A derivatives as potent hepatitis B virus inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 6659–6665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Min, B.; Bae, K. Chemical modification of alisol B 23-acetate and their cytotoxic activity. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2002, 25, 608–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, J.X.; Shen, X.L.; Wan, C.K.; Tse, A.K.W.; Fong, W.F. Reversal of P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance by Alisol B 23-acetate. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004, 68, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.W.; Hsu, M.J.; Chien, C.T.; Huang, H.C. Effect of alisol B acetate, a plant triterpene, on apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells and lymphocyte. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 419, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Qu, H. Study on the hypoglycemic activities and metabolism of alcohol extract of Alismatis Rhizoma. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 1046–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godtfredsen, W.O.; Jahnsen, S.; Lorck, H.; Roholt, K.; Tybring, L. Fusidic acid, a new antibiotic. Nature 1962, 193, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godtfredsen, W.O.; Rastrup-Andersen, N.; Vangedal, S.; Ollis, W.D. Metabolites of Fusidium coccineum. Tetrahedron 1979, 35, 2419–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, R.J.; Schweikert, M.A. Handbook of Secondary Fungal Metabolites, Volume 1; Academic Press: New York, USA, 2003; pp. 461–492. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, M.J.; Hendricks-Gittins, A.; Stacey, L.M.; Adlard, M.W.; Noble, W.C. Fusidane antibiotics produced by dermatophytes. J. Antibiot. 1983, 36, 1659–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.N.; Mendes, R.E.; Sader, H.S.; Castanheira, M. In vitro antimicrobial findin–2009) gram-positive organisms collected in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52 (Suppl. 7), S477–S486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, C.N.; Burnstead, B.W. The safety record of fusidic acid in non-US markets: A focus on skin infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52 (Suppl. 7), S527–S537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, J.C.; Moriarty, S.R.; Clark, K.; Scott, D.; Degenhardt, T.P.; Still, J.G.; Corey, G.R.; Das, A.; Fernandes, P. A randomized, double-blind phase 2 study comparing the efficacy and safety of an oral fusidic acid loading-dose regimen to oral linezolid for the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, S520–S526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, D.J.; Castanheira, M.; Chopra, I. Characterization of global patterns and the genetics of fusidic acid resistance. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, S487–S492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvold, T.; Sorensen, M.D.; Bjoerkling, F.; Henriksen, A.S.; Rastrup-Andersen, N. Synthesis and conformational analysis of fusidic acid side chain derivatives in relation to antibacterial activity. J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44, 3125–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godtfredsen, W.O.; Von, D.W.; Tybring, L.; Vangedal, S. Fusidic acid derivatives. I. Relation between structure and antibacterial activity. J. Med. Chem. 1966, 9, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waksman, S.A.; Horning, E.S.; Spencer, E.L. Production of two antibacterial substances, fumigacin and clavacin. Science 1942, 96, 202–203. [Google Scholar]

- Chain, E.; Florey, H.W.; Jennings, M.A.; Williams, T.I. Helvolic acid, an antibiotic produced by Aspergillus fumigatus, mut. helvola Yuill. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 1943, 24, 108–119. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, A.L.; Gao, J.M. Metabolites from Aspergillus fumigatus, an endophytic fungus associated with Melia azedarach, and their antifungal, antifeedant, and toxic activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 3424–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, M.A. Activity of helvolic acid against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nature 1945, 156, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Ma, Y. Isolation and anti-phytopathogenic activity of secondary metabolites from Alternaria sp. FL25, an endophytic fungus in Ficus carica. Yingyong Yu Huanjing Shengwu Xuebao 2010, 16, 76–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Mou, Y.; Shan, T.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Wang, M.; Wang, J. Antimicrobial metabolites from the endophytic fungus Pichia guilliermondii isolated from Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis. Molecules 2010, 15, 7961–7970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Li, B.; Guan, J.; Zhang, G. In vitro synergistic antibacterial activities of helvolic acid on multi-drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Prod. Res. 2009, 23, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, H.S.; Abraham, E.P. Isolation of antibiotics from a species of Cephalosporium. Cephalosporins P1, P2, P3, P4, and P5. Biochem. J. 1951, 50, 168–174. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, A.C.; Smith, N.; Florey, H.W. Some biological properties of cephalosporin P1. Br. J. Pharmacol. Chemother. 1951, 6, 430–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, A.J.; Bostock, J.M.; Morais, M.A.; Chopra, I. Antimicrobial activity and mechanisms of resistance to cephalosporin P1, an antibiotic related to fusidic acid. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2002, 50, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, T.S.; Eisenbraun, E.J.; Rapala, R.T. Chemistry of steroid acids from Cephalosporium acremonium. Tetrahedron 1969, 25, 3341–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaise, H.; Ogawa, Y.; Sassa, T.; Munakata, K. Chlorosis-inducing substances produced by a fungus. I. Isolation and biological activities of viridominic acids A, B, C, and cephalosporin P1. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1970, 36, 120–124. [Google Scholar]

- Kaise, H.; Munakata, K.; Sassa, T. Structures of viridominic acids A and B, new chlorosis-inducing metabolites of a fungus. Tetrahedron Lett. 1972, 3789–3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.; Hedger, J.N.; Brayford, D.; Stavri, M.; Smith, E.; O’Donnell, G.; Gray, A.I.; Griffith, G.W.; Gibbons, S. An antibacterial hydroxy fusidic acid analogue from Acremonium crotocinigenum. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 2110–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodeiro, S.; Xiong, Q.; Wilson, W.K.; Ivanova, Y.; Smith, M.L.; May, G.S.; Matsuda, S.P.T. Protostadienol biosynthesis and metabolism in the pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 1241–1244. [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuguchi, H.; Seshime, Y.; Fujii, I.; Shibuya, M.; Ebizuka, Y.; Kushiro, T. Biosynthesis of steroidal antibiotic fusidanes: functional analysis of oxidosqualene cyclase and subsequent tailoring enzymes from Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 6402–6411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M.; Kushiro, T.; Shibuya, M.; Ebizuka, Y.; Abe, I. Protostadienol synthase from Aspergillus fumigatus: Functional conversion into lanosterol synthase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 391, 899–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.; Pereira, D. Efforts to support the development of fusidic acid in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52 (Suppl. 7), S542–S546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, M.; Gödecke, T.; Gunn, J.; Duan, J.-A.; Che, C.-T. Protostane and Fusidane Triterpenes: A Mini-Review. Molecules 2013, 18, 4054-4080. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules18044054

Zhao M, Gödecke T, Gunn J, Duan J-A, Che C-T. Protostane and Fusidane Triterpenes: A Mini-Review. Molecules. 2013; 18(4):4054-4080. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules18044054

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Ming, Tanja Gödecke, Jordan Gunn, Jin-Ao Duan, and Chun-Tao Che. 2013. "Protostane and Fusidane Triterpenes: A Mini-Review" Molecules 18, no. 4: 4054-4080. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules18044054