Introduction

Control of product selectivity in organic reactions is a demanding challenge for synthetic chemists. During the past few decades considerable effort has been directed towards altering the selectivity of chemical transformations by organizing the potential reactants in organized media such as micelles, liquid crystals, crown ethers, cryptands, cyclodextrins, monolayers, Zeolites, dendrimer solutions, etc. [

1]. Photochemically triggered reactions are the simplest choice for studying selective chemical transformations in organized media. This is primarily because photochemical reactions can be triggered without any thermal shock that can disturb the structure of organized media.

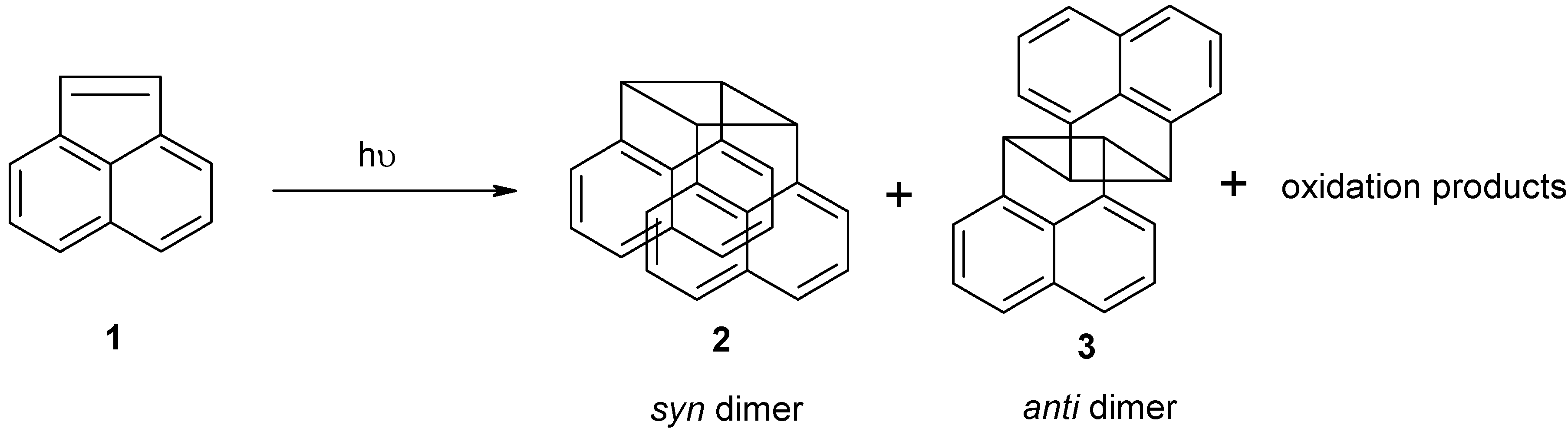

Photodimerization of acenaphthylene (ACN) is a well-known photoreaction which has been studied extensively in the past few decades (

Scheme 1) [

14,

15]. This reaction has previously been investigated in Zeolites, clay environments, polymeric systems, liquid crystalline systems and micellar media. The dimerization process of ACN yields mainly

syn and

anti dimmers, along with minor oxidation products. It has been shown that ACN photodimerization in a micellar medium [for example sodium dodecylsulphate (SDS), Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), etc.] does not affect the isomeric products greatly and the dimer ratios were similar to those observed in water.

Scheme 1.

A photodimerization reaction of CAN.

Scheme 1.

A photodimerization reaction of CAN.

Since the micellar systems are dynamic in nature, they cannot serve as good “reaction vessels.” We are actively involved in the synthesis of gels and we believed that the SAFIN’s (self assembled fibrillar networks) in gels might serve as more rigid reaction vessels. Additionally, extended or enhanced hydrophobic environment in the gel-bound state was considered to be different from a solution or a micellar medium. To the best of our knowledge, gels derived from small molecular weight compounds have not yet been studied extensively as “nanoreactors”. Preliminary results of this work are highlighted in this article.

Results and Discussion

Bile acids and their salts are well-known biological surfactants. They form micellar aggregates that are different from classical long chain alkyl surfactants. Bile salt aggregates have been shown to possess stronger hydrophobic microenvironments compared to alkyl surfactant aggregates. Bile salt aggregates and their interaction with polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) have been studied extensively in the past decades, and these results suggested that the PAH’s were mostly present in the hydrophobic interior of the micellar aggregates [

16]. These findings prompted us to use bile acid based aggregates (gels) to study the photodimerization reaction of ACN.

To study the dimerization reaction of ACN in gel-bound and micelle bound states, ACN was loaded into the gels or micelles (see Experimental section for details). After loading, both gel and solutions in sealed tubes were irradiated with 350 nm UV-irradiation for 12 h. After the reaction the product ratios were analyzed by 1H-NMR. There was no significant change in the photodimer ratios in micelles and the respective solvents studied. A noticeable change however was detected for reactions carried out in gels.

The photodimerization of ACN in hydrogel was studied up to 10 mol% loading. Higher loading of the reactant was difficult because of its limited aqueous solubility. In this ACN concentration range (0.03 – 3.0 mM) there was no significant change in the product ratios. The product ratios calculated from

1H-NMR (the cyclobutane-H was monitored, see

Figure 1) for ACN photodimerization reaction in hydrogels were 3-10 times higher in magnitude compared to the reactions in micellar solutions (

Table 1).

Figure 1.

1H-NMR spectrum of syn (bottom) and anti (top) dimers of ACN obtained in CDCl3. A cyclobutane-H signal (circle, δ value for syn dimer 4.837; for anti dimer 4.095) was monitored for analyzing the isomeric ratios.

Figure 1.

1H-NMR spectrum of syn (bottom) and anti (top) dimers of ACN obtained in CDCl3. A cyclobutane-H signal (circle, δ value for syn dimer 4.837; for anti dimer 4.095) was monitored for analyzing the isomeric ratios.

Figure 2.

Structure of the gelators used for making the gels to carry out photodimerization.

Figure 2.

Structure of the gelators used for making the gels to carry out photodimerization.

The dimerization reaction was carried out using different hydrogelators (

Figure 2, gelators

4-

7) to see the general applicability of the reaction. These hydrogelators have been studied by us previously. It was found that the product ratios of the dimers were strongly dependent on the properties of the gels. A very strong or rigid gel showed the highest product selectivity. The rigidity of the gels and the product selectivity followed the sequence

6>

5>

7>

4 [

17].

Table 1.

Results obtained from acenaphthylene dimerization reaction in different hydrogels.

Table 1.

Results obtained from acenaphthylene dimerization reaction in different hydrogels.

| Reactant | Reaction medium | Gelator concentration (% w/v) | anti / syn dimer ratio |

|---|

| ACN | 20% AcOH/H2O | - | 0.7 |

| ACN | Gel of 4 a | 1.2 | 2.0 |

| ACN | 1 M NaCl | - | 0.9 |

| ACN | Gel of 5 b | 0.5 | 5.0 |

| ACN | 0.5 M NaCl | - | 1.0 |

| ACN | Gel of 6 c | 0.4 | 11 |

| ACN | Phosphate buffer d | - | 1.3 |

| ACN | Gel of 7 e | 1.2 | 3.5 |

While the effect of the gel on the photodimer ratio is clear, the origin of this effect is harder to understand. Clearly, the lower solvent accessible surface of the

syn-dimer is not playing any role. Though the quantum yield of acenaphthylene is very small (~1 x 10

-4), the emission spectra of ACN were recorded in the gel-bound sate and in micellar solution, to obtain information on the interaction between the gelator and ACN [

18] (

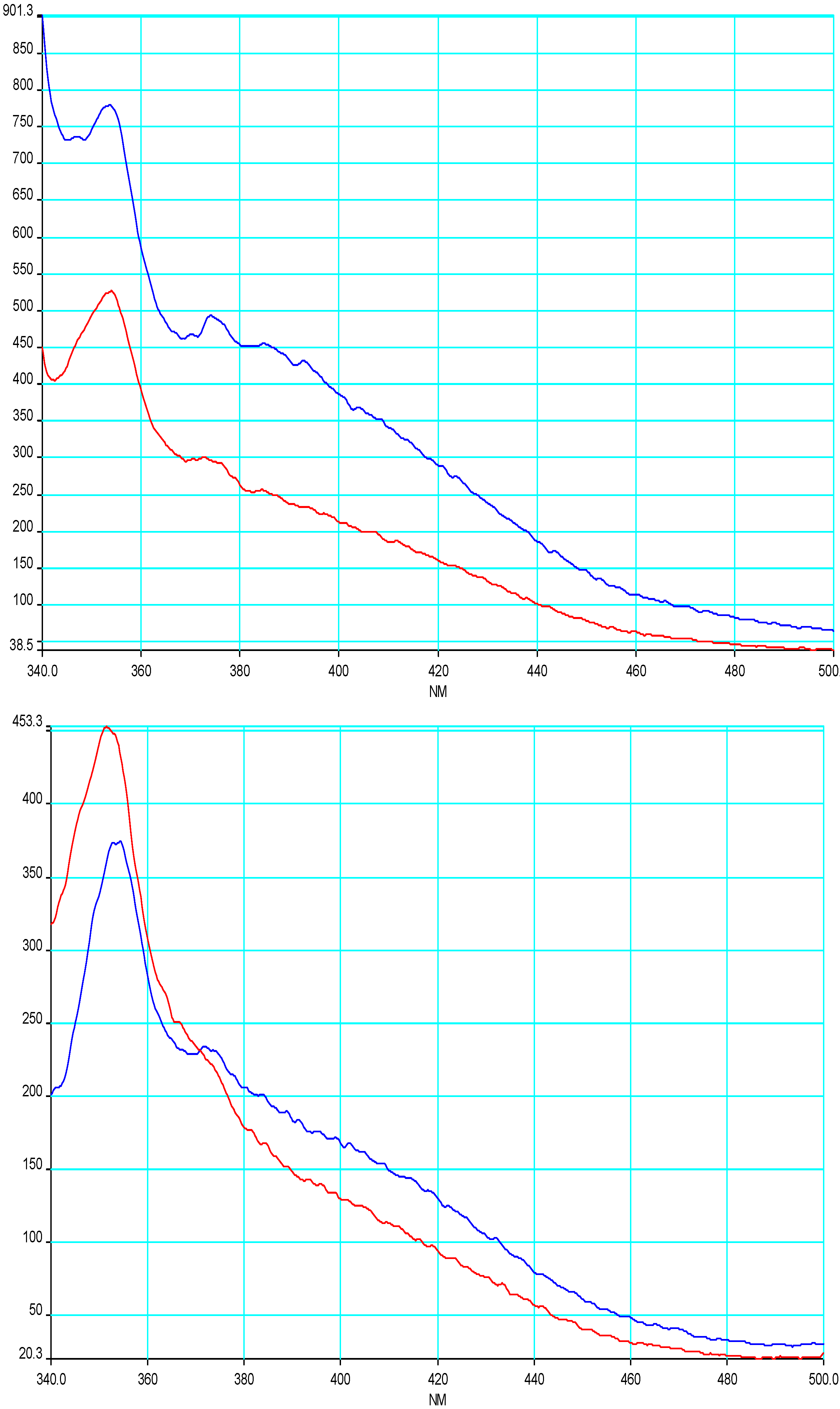

Figure 2).

Fluorescence self-quenching was observed upon increasing the acenaphthylene concentration (0.18 to 1.0 mM) in gel/solution. This observation is similar to solutions in hexane, which also showed a similar concentration dependent quenching. The intensity of the excimer band of ACN was different in micellar solution and in gel. At low ACN concentration the excimer emission was stronger than in solution. At larger concentrations of ACN, both the monomer and excimer fluorescence were quenched.

However, the emission spectrum of ACN in water showed no detectable excimer emission (as observed for naphthalene). The absence of an excimer band does not completely rule out the existence of ground state pairs, since the concentration of the ground state pairs could be too low to be observed through the excimer emission. The excimer is a presumed precursor to

syn dimer formation from S

1, so failure to observe excimer emission suggests that ACN ground state pairs in a less than ideal orientation would not lead to dimer upon photolysis [

19].

Figure 2.

Emission spectrum of ACN in solution (red line) and gels (blue line) of 4 (11.5 mM) at 0.18 mM (upper) and 0.93 mM (lower).

Figure 2.

Emission spectrum of ACN in solution (red line) and gels (blue line) of 4 (11.5 mM) at 0.18 mM (upper) and 0.93 mM (lower).

Experimental

General

Acenaphthylene was obtained from Aldrich and recrystallized from methanol prior to use. Gelators

4,

5 and

6 were synthesized using our own methodology [

17,

20]. NaDC (gelator

7) was purchased from Aldrich (Lot 117F0022). A Rayonet photoreactor fitted with UV lamps (350 nm) was used for photolysis. A Shimadzu UV-2100 spectrophotometer and a Perkin-Elmer LS-50B luminescence spectrometer were used for absorption and fluorescence measurements, respectively. All other chemicals and solvents were ACS or reagent grade. Double distilled solvents were used for all spectral measurements. The glassware was acid washed prior to use.

Sample preparation and reactant loading

The samples were prepared by stirring the reactants in suitable solvents (AcOH/H2O, aq. NaCl, and/or phosphate buffer purged previously with nitrogen) for 24 h. The suspensions were filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper (2 μm). The concentration of the reactant (ACN) was determined by measuring its UV absorbance. A clear solution of filtrate containing the reactants was used to prepare the gel. The gels were kept in the dark at room temperature (27 °C) for at least 2 h for stabilization before irradiation.

Photolysis

The ACN samples were taken in a Pyrex glass tube (l. 15 cm, d. 0.9 cm) fitted with a B-14 joint. Photolysis of the samples was carried out using 350 nm UV-lamps inside a Rayonet photoreactor for 12 h. After irradiation, the photoproducts formed were extracted into chloroform. The chloroform layer was washed with dil. HCl, aq. NaHCO3 and water to remove all water-soluble species. Finally, the organic layer was dried over anhyd. Na2SO4, and after removing the chloroform, the photo products were analyzed by 1H-NMR spectroscopy in CDCl3 without further purification. The spectra were compared with the data obtained from the pure dimers.

Analysis of the photoproducts

Photoproducts of ACN were analyzed by 1H-NMR. Acenaphthylene dimers show characteristic cyclobutane proton signals, which is a singlet. The dimer ratios (anti/syn) were determined by comparing the integration value of this signal.

Preparation of authentic syn and anti dimers of acenaphthylene by the photolysis method

Acenaphthylene (0.1 g, 0.66 mmol) was dissolved in AcOH (10 mL) and diluted with double distilled water (3 mL). This clear solution was transferred into a stoppered pyrex test tube. The solution was photolyzed using 350 nm UV lamps in a Rayonet photoreactor for 30 h. Out of the two possible dimers, one crystallized out and was identified as 90%

anti by comparing its

1H-NMR chemical shifts with the reported values. Pure

anti and

syn dimmers were isolated by flash column chromatographic separation using 10-20% CHCl

3/pet.ether as the eluent (16 mg of

syn-ACN dimer, 10 mg of

anti-ACN dimer, with total conversion of about 30% determined from

1H-NMR). Other photo-oxidation products were formed in very minor quantities.

1H-NMR spectra of the pure isomers are shown in

Figure 1.

Photodimerization of ACN in 20% AcOH/water and in the gel derived from 4

A 1.0 mM solution of ACN (5 mg, 0.03 mmol) was prepared by dissolving in AcOH (4.0 mL) and diluting with distilled water (20 mL). The suspension was sonicated for at least 20 min. (0.01 mmol; ~10% loading of the reactant was maintained). The clear solution (10 mL) was mixed with gelator 4 (120 mg, 0.09 mmol) and dissolved by warming. The hot sol containing ACN was allowed to cool and form a strong gel (no flow of the fluid upon inversion of the tube) at 27 °C. The remaining 10 mL of the solution was transferred into a similar tube as a control. Both of the samples were sealed and irradiated with 350 nm UV-light in a Rayonet photoreactor for 12 h. After photolysis, the gel was heated to a sol and the photoproducts were extracted (4 x 5 mL) into chloroform. The chloroform layer was washed with dil. HCl to remove the gelator and other impurities followed by washing with distilled water (5 mL). Finally, the organic layer was dried over anhyd. Na2SO4 and chloroform was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in 0.6 mL of CDCl3 and analyzed by 1H-NMR.

Photodimerization of ACN in cationic bile salt gels and their micellar solution

ACN (10 mg, 0.065 mmol) crystals were added to 0.5 M NaCl solution (25 mL) and sonicated for 20 min. The resulted suspension was filtered using Whatman No. 1 filter paper. The concentration of the ACN in the filtrate was determined by measuring the UV-absorbance, which was about (0.6 mg, 0.004 mM). The filtrate (10 mL) was mixed with the cationic gelator (37.5 mg of 5, 0.06 mmol; or 30 mg of 6, 0.08 mmol) and warmed to dissolve. The hot sol was allowed to stabilize for 2 h (loading of the reactants was kept around 3-4%). The remaining solution (10 mL) was mixed with the gelator 6 (6 mg, 0.012 mmol of 6 or 9.5 mg, and 0.02 mmol of 5 to obtain the micellar solutions) taken in a pyrex tube which was stoppered. Both of the samples were photolyzed for 12 h with 350 nm UV-lamp in a Rayonet photoreactor. After photolysis, the photoproducts were extracted into chloroform (3 x 5 mL) and washed with distilled water (2 x 5 mL). The organic layer was dried over anhyd. Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in CDCl3 (0.6 mL) and analyzed by 1H-NMR.

Photodimerization of ACN in sodium deoxycholate gel (NaDC, gelator 7)

Phosphate buffer (pH 6.9) was prepared by adjusting the volumes of 0.5 M Na2HPO4, and 0.5 M KH2PO4 solutions. ACN crystals (10 mg, 0.065 mmol) were added to phosphate buffer (25 mL) and sonicated for 20 min. The resultant suspension was filtered using Whatman No. 1 filter paper, and the concentration of ACN was determined by measuring its UV-absorbance (0.6 mg, 0.004 mM). The filtrate (10 mL) was mixed with NaDC.H2O (NaDC - Sodium deoxycholate, 120 mg, 0.09 mmol) and sonicated for 1 min to obtain the gel. The gel was allowed to stabilize for 2 h. The remaining solution (10 mL) was used to prepare micellar solution of NaDC (21.6 mg, 0.05 mmol). Both the tubes containing the gel and micellar solutions loaded with ACN were sealed and photolyzed for 12 h. After photolysis, photoproducts were extracted into chloroform (4 x 5 mL) and washed with NaHCO3 solution (2 x 5 mL) followed by distilled water wash (2 x 5 mL) to remove bile salt impurities. The organic layer was dried over anhyd. Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue obtained was dissolved in 0.6 mL of CDCl3 and analyzed by 1H-NMR.