1. The Individual in Modern Sociology

Sociological theories can be categorised by the way they relate structures and actors [

16]. Individualistic and subjectivistic theories consider the human being as an atom of society and society as the pure agglomeration of individual existences. Structuralistic and functionalistic theories stress the influence and constraints of social structures on the individual and actions. Dualistic sociological theories conceive the relationship of actors and structures as independent, arguing that actors are psychological systems that don’t belong to social systems. Finally, dialectical approaches try to avoid one-sided solutions of this foundational problem of sociology and conceive the relationship of actors and structures as a mutual one.

Functionalist and structuralistic positions are unable to see human beings as reasoning, knowledgeable agents with practical consciousness and argue that society and institutions as subjects have needs and fulfil certain functions. This sometimes results in views of a subjectless history that is driven by forces outside the actors’ existence that they are wholly unaware of. The reproduction of society is seen as something happening with mechanical inevitability through processes of which social actors are ignorant. Functionalism and structuralism both express a naturalistic and objectivistic standpoint and emphasise the pre-eminence of the social whole over its individual, human parts. Mechanistic forms of stucturalism reduce history to a process without a subject and historical agents to the role of supports of the structure and unconscious bearers of objective structures (Althusser).

In individualistic social theories structural concepts and constraints are rather unimportant and quite frequently sociality is reduced to individuality. There is a belief in fully autonomous consciousness without inertia. E.g. methodological individualists such as von Mises, Schumpeter and Hayek claim that social categories can be reduced to descriptions of the individual. “If interpretative sociologies are founded, as it were, upon an imperialism of the subject, functionalism and structuralism propose an imperialism of the social object” [

18: p. 2].

In Hegelian terms, individualism reduces society to individual being-in-itself or abstract, pure-being, whereas structuralism and functionalism consider the role of the human being in society merely as being-for-another and determinate-being. Only dialectical approaches to society consider the importance of both aspects, unity as being-in-and-for-itself. Already Hegel criticised atomistic philosophies [

21: §§ 97, 98] by saying that they fix the One as One, the Absolute is formulated as Being-for-self, as One, and many ones. It doesn’t see that the One and the Many are dialectically connected: the One is being-for-itself and related to itself, but this relationship only exists in relationship to others (being-for-another) and hence it is one of the Many and repulses itself. But the Many are one the same as another: each is One, or even one of the Many; they are consequently one and the same. As those to which the One is related in its act of repulsion are ones, it is in them thrown into relation with itself and hence repulsion also means attraction.

Also Marx criticised the reductionism of individualism in his critique of Max Stirner [

32: p. 101-438) and put against this the notion of the individual that is estranged in capitalism and that can only become a well-rounded individual in communism. Stirner says that the individual can only be free if it gets rid of dominating forces such as religion, state, and even society and humankind. He argued in favour of a “union of egoists” and stressed the superiority of the individual and the uniqueness of the ego. Social forces would be despotic, they would limit and subordinate the ego of the individual.

Marx interposes that: 1. individualism doesn’t see the necessarily social and material interdependence of individuals and doesn’t grasp their process of development because it limits itself to advise them that they should proceed from themselves. “Individuals have always and in all circumstances “proceeded

from themselves”, but since they were not

unique in the sense of not needing any connections with one another, and since their needs, consequently their nature, and the method of satisfying their needs, connected them with one another (relations between the sexes, exchange, division of labour), they

had to enter into relations with one another” ([

32: p. 423]).

2. Individualism wouldn’t adequately reflect the real conflicts in the world and due to an idealistic inversion of the world it would replace political praxis by moralism. Stirner wants to do away with the “private individual” for the sake of the “general”, selfless man, but consciousness is separated from the individual and its existence in the real, material world. Marx: “It depends not on

consciousness, but on

being; not on thought, but on life; it depends on the individual’s empirical development and manifestation of life, which in turn depends on the conditions obtaining in the world. If the circumstances in which the individual lives allow him only the [one]-sided development of one quality at the expense of all the rest, [If] they give him the material and time to develop only that one quality, then this individual achieves only a one-sided, crippled development. No moral preaching avails here” ([

32: p. 245f).

Individualism has had its rise with the emergence of modern, i.e. capitalist society and is related to ideas that have been developed during the course of the enlightenment such as a free will as well as rationally and responsible acting subjects. The enlightenment formed an integral element of the process of establishing modern society. The concept of the modern individual is also one that has been made possible by questioning religious eschatologies of an unalterable and God-given fate of humankind. The rise of this modern notion of the individual has also been interrelated with the rise of the idea of “free” entrepreneurship in market society. Freedom has been conceived in this sense as an important quality and essence of the modern individual. The idea of the modern individual can be seen as a logical consequence of the liberal-capitalist economy. According to this concept, morally responsible and autonomous personalities can develop on the basis of economical and political freedom that is guaranteed by modern society. It also stresses that society guarantees individuality by removing obstacles to individual freedom and to rational and reasonable actions. In the ideology of individualism, individuality is clearly identified with following self-interest economically. Egoism and selfishness are often fetishised by assuming that they are natural characteristics of all individuals and that they emerge from rational and autonomous thinking. But it can also be argued that our modern society is not reasonable because it does not guarantee happiness and satisfaction of all human beings, in fact these categories are only achievable for a small privileged elite.

Nowadays individuals are not only seen as owners of a free will, it is also generally assumed that this free will can be applied in order to gain ownership of material resources and capital which makes it possible to realise individual freedom. So freedom is seen as something that can be gained individually by striving towards individual control of material resources. This shows that the concept of the modern individual is unseparately connected with the idea of private property. The idea of the individual as an owner has dominated the philosophical tradition from Hobbes to Hegel and still dominates philosophical ideas about the essence of mankind. But this concept has never be applied to all humans that are part of society because the majority of the world population still does not possess all these idealistically constructed aspects of freedom and autonomy, this majority is rather confronted with alienation and the disciplinary mechanisms of compulsions, coercion and domination. Hence the modern idea of the individual can be seen as an ideology that helps to legitimate modern society. The idea of already existing autonomous individuals may be a nice ideal, but nonetheless it can today be seen as nothing more than imagination and self-deception.

Besides individualism and structuralism, there is also dualism. In sociology, the main representative of the sciences of complexity is Niklas Luhmann. Luhmann argues that action-based conceptions of society are reductionistic because they reduce social order to rational human beings and that they can’t adequately explain the increasing complexity of modern society as well as emergent properties of social systems [

24]. Luhmann wrongly infers from this that the explanation of social relationships should neglect acting human subjects. This results in a dualistic theory that due to the neglect of human subjects itself can’t adequately explain the bottom-up-emergence of social structures and the top-down-emergence of actions and behaviour.

Luhmann argues that self-reproduction is a necessity of a social system that is not based on human actions, conceives society in functional terms, applies Maturana’s and Varela’s autopoiesis-concept sociologically and sees society as a self-referential system with communications as its elements. He argues that individuals are (re)produced biologically, not permanently by social systems. If one wants to consider a social system as autopoietic or self-referential, the permanent (re)production of the elements by the system is a necessary condition. Hence Luhmann says that not individuals, but communications are the elements of a social system. A communication results in a further communication, by the permanent (re)production of communications a social systems can maintain and reproduce itself. Luhmann can’t explain how one communication can exactly produce other communications without individuals being part of the system. An autopoietic conception of society must show consistently that and how society produces its elements itself. Luhmann does not show how communications are produced, he only mentions that communications result in further communications. He can explain that society is self-referential in the sense that one communication is linked to other ones, but he can’t explain that it is self-producing or autopoietic.

A consistent alternative that bridges the shortcomings of individualism, structuralism and dualism is a dialectical theory of society.

2. What Is an Individual?

Social systems science has been massively influenced by the functionalist traditions of Talcott Parsons and Niklas Luhmann. Functionalism underestimates the role of the individual in social systems and does not take into account that society can only reproduce itself by social actions that are formed by individuals entering social relationships. Niklas Luhmann [

24] argues that social systems are self-referential ones that reproduce themselves by self-referential communication. Communications are considered as the elements of social systems, individuals are only seen as sensors on the outside of the system. This also results in the dualistic conception that psychological and social systems do not overlap.

An individual is a self-conscious and social being. It has the ability to consciously create new qualities, to reflect about its actions and to select one action from several possible ones. It can consciously repeat past actions and actively plan future situations. It can reflect its own and other actions, draw conclusions from it and apply them to future actions. Human beings are social beings, they enter social relationships which are mutually dependent actions that make sense for the acting subjects. Individual being is only possible as social being, social being is only possible as a relationship of individual existences. This dialectic of individual and social being has been pointed out by Marx: “The individual

is the social being. His manifestations of life – even if they may not appear in the direct form of communal manifestations of life carried out in association with others – are therefore an expression and confirmation of

social life. Man's individual and species-life are not

different, however much – and this is inevitable – the mode of existence of the individual is a more

particular or more general mode of the life of the species, or the life of the species is a more

particular or more general individual life“ [

26: p. 538f]. Man is the subjective existence of society and he exists as a totality of human manifestation of life.

Marx says that social analysis has to begin with “individuals producing in a society” [

28: p. 615), these individuals are “dependent and [...] belong to a larger whole” (p. 616). He considers man as a zoon politikon (political animal) that is not only a social animal, but an animal that can be individualised only within society. Man would be a social being, the concept of a “solitary individual outside society” would be preposterous.

For Marx the individual is of great importance in his social analysis, not as an isolated atom, but as a social being that is the constitutive part of qualitative moments of society and has a concrete and historical existence. “The first premise of all human history is, of course, the existence of living human individuals” [

32: p. 20]. He considers the individual in its abstract being-for-self, its connectedness to others and its estrangement in modern, capitalist society. The individual as a social, producing being (“individuals co-operating in definite kinds of labour“) results in phenomena such as modes of life, increase of population (family), forms of intercourse (Verkehrsformen), separation of town and country, forms of politics (nation state), division of labour, forms of ownership (tribal ownership, ancient communal and State ownership, feudal or estate property (feudal landed property, corporative movable property, capital invested in manufacture, capital as pure private property), production of ideas, notions and consciousness. For Marx, a certain mode of production is combined with a certain mode of co-operation [

32: p. 30] and the history of humanity is closely connected to the history of the economy. Opposing the atomism of Max Stirner and Bruno Bauer, Marx writes that the “individuals certainly make one another, physically and mentally, but do not make themselves” [

32: p. 37].

In the

German Ideology [

32], Marx speaks of social relationships as forms of intercourse, whereas he later replaced this term by the one of relationships of production. He says that with the development of the productive forces, the form of intercourse becomes a fetter and in place of it a new one is put which corresponds to the more developed productive forces and hence “to the advanced mode of the self-activity of individuals” – a form which in its turn becomes a fetter and is then replaced by another one etc. The history of the forms of intercourse would be the history of the productive forces and hence the history of the development of the forces of the individuals themselves [

32: p. 72].

Social systems are always human systems. Certain scientist like Maturana claim that also some animals are social beings. Maturana argues that the essence of a social being is emotional attitude towards others and mutual acceptance (“love” in Maturana’s terms). We certainly find these aspects to a certain degree also in the world of higher animals. Defining the term “social” not solely with respect to the human world results in the problem that one has to draw a border in the animal world that shows which animals are social and which are not. This might not be a very easy undertaking and in fact people like Maturana simply neglect this problem. Another problem is that the qualitative leap between humans and animals is somehow blurred, suggesting that humans are nothing else than some special form of animals. From an ethical point of view this can be dangerous because if the human being is not seen as a value as such and as something to a large extent entirely different from all other existence, this can result in the downgrading or biologisation of man. Biologism might enter sociology again (as the example of the biologist Maturana trying to speak about social systems shows) which is very dangerous as history and the influence of Social Darwinism on fascist ideologies has shown.

The behaviour of animals is largely based on instinct, although learning exists in a certain, limited extent. The range and complexity of learned behaviour in human beings is by far greater than in any animal. Chimpanzees have a considerable learning capacity in comparison to other animals, but as experiments show they completely lack a comparison to human learning capabilities. In contrast to all animals, the behaviour of humans is not genetically programmed and led by instincts. Humans rely much more on learned and socialised patterns of behaviour. The plurality of human culture shows that the human genetic code does not contain specific instructions to behave in certain ways. You won’t find this plurality concerning e.g. nests built by birds, dwellings built by apes etc.

Sociality does not only simply mean that some beings act together in order to achieve something. Already Max Weber pointed out in his fundamental definitions of sociological categories, that in a social system we always find the production of meaning. He argued that all human action is directed by meanings. Actions have a specific meaning for the actors, they can make sense of the world. Social actors have motives, they can identify reasons for their actions and have planned intentions in concrete situations. They can choose between different alternative actions in a situation, they can consciously reflect the state of the world (and its change) and can identify their role and position in the world. Human beings can interpret social situations in different ways, by this meaning (the definition of situations by actors) is produced. So making sense of the world involves planned actions, reflection, the identification of reasons for actions, intentions, freedom to choose between different alternative actions, identification of ones own role in the world and (different) interpretations of the world. All sociality involves the production of sense and this has to do with self-consciousness. Animals do not have self-consciousness and they cannot make sense of the world. Hence one would not describe birds building a nest, working bees or chimpanzees playing together with the terms “social” or “sociality”. Both concepts are solely related to the human realm.

Human beings begin to distinguish themselves from animals by starting to produce their means of subsistence by which they are indirectly producing their actual material life ([

32: p. 21]). Marx pointed out that man like animals lives from inorganic nature, he must remain in a continuing physical dialogue with nature in order to survive. Animals produce only their own immediate needs, “animals produce one-sidedly, whereas man produces

universally; they produce only when immediate physical need compels them to do so, while man produces even when he is free from physical need and truly produces only in freedom from such need; they produce only themselves, while man reproduces the whole of nature; their products belong immediately to their physical bodies, while man freely confronts his own product. Animals produce only according to the standards and needs of the species to which they belong, while man is capable of producing according to the standards of every species and of applying to each object its inherent standard; hence, man also produces in accordance with the laws of beauty“ ([

26: p. 517]). In the production of his life that includes the metabolism between society and nature and social reciprocity, man as the universal, objective species-being produces an objective world (gegenständliche Welt) and reproduces nature and his species according to his purposes. With the human being, history emerges: “the more that human beings become removed from animals in the narrower sense of the word, the more they make their own history consciously, the less becomes the influence of unforeseen effects and uncontrolled forces of this history, and the more accurately does the historical result correspond to the aim laid down in advance“ ([

10: p. 323]). “The animal merely

uses external nature, and brings about changes in it simply by his presence; man by his changes makes it serve his ends,

masters it. This is the final, essential distinction between man and other animals, and once again it is labour that brings about this distinction” ([

9: p. 452]).

As Friedrich Engels [

9,

10] has shown, the break-up of immediacy of behaviour (which is a foundation of the emergence of society) started with the erect posture in walking which resulted in the specialisation of the hand which implies tools, tools imply production as human activities that transform nature. A differentiation of certain bodily forms can result in other organic differentiations. The specialisation of the hand resulted in labour and the utilisation of nature. The emergence of labour and production resulted in a co-evolution of society and consciousness. The genesis of man is due to a dialectic of labour and human capabilities (hand, language, increase of brain volume, consciousness etc.) which resulted in developments such as hunting, stock farming, agriculture, metal processing, navigation, pottery, art, science, legislation, politics etc. Idealistic conceptions of the development of man argue that consciousness existed prior to human beings as beings in society as has been done in traditional philosophy of consciousness. Symbolic interactionism (e.g. George Herbert Mead) on the other hand has pointed out that the development of consciousness can only be explained by assuming social interactions and social actions mediated by the usage of symbols. Both explanations are reductionistic, they assume either consciousness or society as determining the historical process. The emergence of the individual as a social being can only be explained adequately by a dialectical co-evolution of society (especially categories such as labour and production) and human abilities.

By interacting and entering social relationships, individuals frequently exchange and generate symbols. The generation of symbols that are basic representations of parts of the world, is a social process and takes place within the framework of social relationships. Symbols gain meaning by cultural signification and influence individual lifestyles, ways of life and thinking.

As pointed out by Marx, man is also a species-being – not only in the sense that he reproduces the species biologically, but also in the sense that he lives from inorganic nature and natural products. “Nature is man’s inorganic body – that is to say, nature insofar as it is not the human body. Man lives from nature – i.e., nature is his body – and he must maintain a continuing dialogue with it if he is not to die” [

26: p. 516]. Unlike the animal, man has conscious life activity. The animal produces only its own immediate needs, whereas man (re)produces himself and the whole of nature universally and this results in the practical human creation of an objective world. Modern society has estranged man from himself and nature, this results in the exploitative appropriation of both, life has become alienated life.

So Marx already described man as a self-reproducing being: this does not only mean the internal autopoietic self-reproduction of the organism as suggested by Maturana and others, it also means an external, social as well as natural type of self-reproduction: man reproduces himself by social activities and by exchanging matter and energy with his natural environment (=labour). Material production, social activities and a relationship between man and nature are necessary for the self-reproduction of man and the reproduction of the whole of society and nature by human activities. The aspect of the conscious reproduction of the man-nature-relationship is grasp by the concept of the species-being.

Human beings exchange matter and energy with their natural environment. Labour is a social process that results in the production of use-values and social resources that are useful for humans, satisfy human needs and are produced in order to simplify existence and achieve defined goals. Labour is only possible as an active shaping of nature and the world, man appropriates nature in order to produce use values. In this sense man is an active natural being. The relationship between man and nature is mediated by technologies. Humans produce technologies in order to better organise the labour process. Technology can be defined as a purposeful unity of means, methods, abilities, processes and knowledge that are necessary in order to achieve defined goals. Humans have the ability to consciously think about their environment, to set themselves self-defined goals and to find different ways to achieve these goals. Technologies mediate the reaching of human goals and the social labour process.

Humans make use of objects in the world and they actively create new objects in the labour process. Hence man is objective man. In this process, his living labour power is being objectified in use values that are a type of dead labour that store information about the world and society. This objectivity of human existence also finds an expression in the fact that all human organs and senses are in their

orientation to the object, the appropriation of the object, the appropriation of human reality [

26: p. 539]. So the objective world becomes the world of man’s essential powers for man in society and “all

objects become for him the

objectification of himself, become objects which confirm and realise his individuality, become his objects: that is, man

himself becomes the object” [

26: p. 541]. Man is a

corporeal, living, real, sensuous, objective being that has real, sensuous objects as the object of his being, he can only express his life in real, sensuous objects.

Man exists within and by the use of language and the exchange of symbols. Interacting by language is also one of the necessary conditions for man as a cultural being. Culture involves the whole ways of life, man’s ways of thinking and acting and the emergence of social norms and values. Socially accepted and established norms are guidelines that direct conduct in particular situations. Norms define acceptable and appropriate behaviour in particular social situations. Domination refers to the disposition over the means of coercion required to influence others or processes and decisions. Domination always includes sanctions, repression, threats of violence and an asymmetric distribution of power. Power can be regarded as the disposition over the means required to influence processes and decisions in one’s own interest. In societies that are imprinted by domination, norms are usually enforced by positive and negative sanctions that may be formalised or not. Values are more general guidelines than norms. Socially established and accepted values are believes that something is good and desirable. They define what is considered as important and worth striving for. Human beings have the ability to create norms, values, habits, traditions and different ways of life and their behaviour is influenced and imprinted by existing cultural modes. As typical expression of cultural activities, man creates cultural manifestations such as art, literature, music, science, ideologies, world outlooks etc.

We already mentioned that creativity is a basic skill of the individual. Creativity means the ability to create something new that seems desirable and helps to achieve defined goals. Man can create images of the future and actively strive to make these images become social reality. Man has ideals, visions, dreams, hopes and expectations that are based on the ability of imagination which helps him to go beyond existing society and to create alternatives for future actions. Based on creativity, man designs society [

2]: Design is a future-creating human activity that goes beyond facticity, creates visions of a desirable future and looks for a solution to existing problems. Design creates new knowledge and findings. Man designs machines, tools, theories, social systems, physical entities, nature, organisations etc. within social processes.

Man as creative being is also self-creative, because modern man has been the result of the active human transformation of society and nature, no external metaphysical forces were at play. Human beings have the ability to create their own history depending on the constriction and influence of the existing social forces and relationships. Society is the result of human activity and is not a static being, it is dynamically becoming by the influence of the relationships humans enter and the relationships of these social relationships.

Due to man as a self-conscious, active and creative being, he can strive towards freedom and autonomy. Freedom includes the absence of dominating and controlling forces and the possibility for individuals and groups to choose and design the conditions of their own life all by themselves. This means freedom in terms of self-determination, a maximum of participation and man’s control over himself. Freedom is always not only a individual, but also a collective category because the individual can only be free if a maximum of self-determination for all others can be achieved and collective or social freedom can only be reached when a maximum of individual autonomy (the possibility to choose one’s own way of life and interests that do not conflict with other lifestyles and interests) is enforced. There is no individual without collective freedom and no collective freedom without a maximum of individual autonomy. Collective and individual freedom is not automatically given, but are something that man has the ability to desire and to achieve.

The individual as a social being must co-operate with others to a certain extent in order to exist. Co-operation can be seen as a social relationship in which the mutual references of the involved individuals (these are social interactions) enable all of them to benefit from the situation. By co-operating individuals can reach goals they would not be able to reach alone.

Co-operation is a topic that has been widely ignored in traditional sociology. Marx defined co-operation as numerous labourers working together side by side, whether in one and the same process, or in different but connected processes [

31: p. 344]. He was right that co-operation means working consciously together, but this is not only an economic, rather a universal social phenomenon. Co-operation is not confined to a single branch of society, it is a universal principle in all subsystems, including besides the economy also politics, culture, media, education, art etc. Besides that co-operation is today not only a compulsion and something that can solely be found in the industrial labour process, co-operation is a collective process that makes use of the auto-creativity and re-creativity of social systems in order to achieve defined goals more efficiently.

Schmidt/Bannon [

35] argue that mutual dependence is a condition for co-operation: “people engage in co-operative work when they are mutually dependent in their work and therefore are required to co-operate in order to get the work done. [...] Being mutually dependent in work means that A relies positively on the quality and timeliness of B’s work and vice versa” [

35: p. 13]. They say that co-operation always means that a task can’t be reached individually. But in reality, some tasks might be reached individually, but actors engage in co-operative relationships because they can achieve goals more efficiently and more quickly together with others who share the same assumptions and goals, although the tasks might also be reached individually. It is not true that necessarily “the reason for the emergence of co-operative work formations is, of course, that workers could not accomplish the task in question if they were to do it individually” ([

35: p. 14]). Maybe they could accomplish it alone, but they find co-operation more attracting.

Co-operation involves some sort of shared goals and can be accomplished across spatial and temporal distances because modern technologies enable the disembedding and reembedding of social relationships, they cause and overcome time-space distanciation of social relationships, including co-operative social relationships. Co-operation involves mutual learning and mutual aid. Co-operation means social situations and processes where human actors co-ordinate their actions and communications in such a way that the social system makes use of its re-creativity and creates a new reality that represents a shared goal. This result can due to co-operation be reached more effectively and efficiently than in an individual situation. The co-operating actors have to a certain extent shared goals, they agree upon certain conventions and communicate about goals and convention in order to reach a common understanding. Co-operation means that actors communicatively make concerted use of existing rules and resources in order to create new rules and resources. Rules and resources (structures) are medium and outcome of co-operation. By co-operating, actors mutually benefit from each other, i.e. co-operation means communicative settings with positive “symbiotic” relationships.

New qualities of a social system can emerge by social co-operation. The elements/individuals of this system are conscious of these structures that cannot be ascribed to single elements, but apply to the social whole which relates the individuals to each other. Such qualities are constituted in a collective process by all concerned individuals and are emergent qualities of social systems. Social competition can bee seen as a social relationship in which the social interactions as well as the relationships of power and domination enable some individuals or social sub-systems to take advantage of others. The first benefit at the expense of the latter, who have to deal with the disadvantages of the situation. Co-operation is a way of designing social relationships that is necessary to a certain extent for individuals to exist, whereas competition is an artificial mode of shaping social relationships.

Summing up it can be said that the individual is a social, self-conscious, creative, producing, reflective, cultural, symbols- and language-using, active natural, labouring, objective, corporeal, living, real, sensuous, visionary, imaginative, designing, co-operative being that makes its own history and can strive towards freedom and autonomy.

3. The Relationship of Actors and Social Structures

One of the basic questions of sociology is the one about the relationship between social structures and social actions. Traditionally it has been solved in a reductionist manner: Action Theory and Symbolic Interactionism (Max Weber, George Herbert Mead, Jürgen Habermas etc.) argue that society and social systems are constituted by social actions whereas Structuralism and Functionalism (Emil Durkheim, Robert Merton, Talcott Parsons, Niklas Luhmann etc.) see the basic social process as the structuring of thinking and actions by existing social structures. Action Theory underestimates the structural constraining of social actions whereas functionalist theories often do not leave enough room for a certain degree of freedom of actions and thinking.

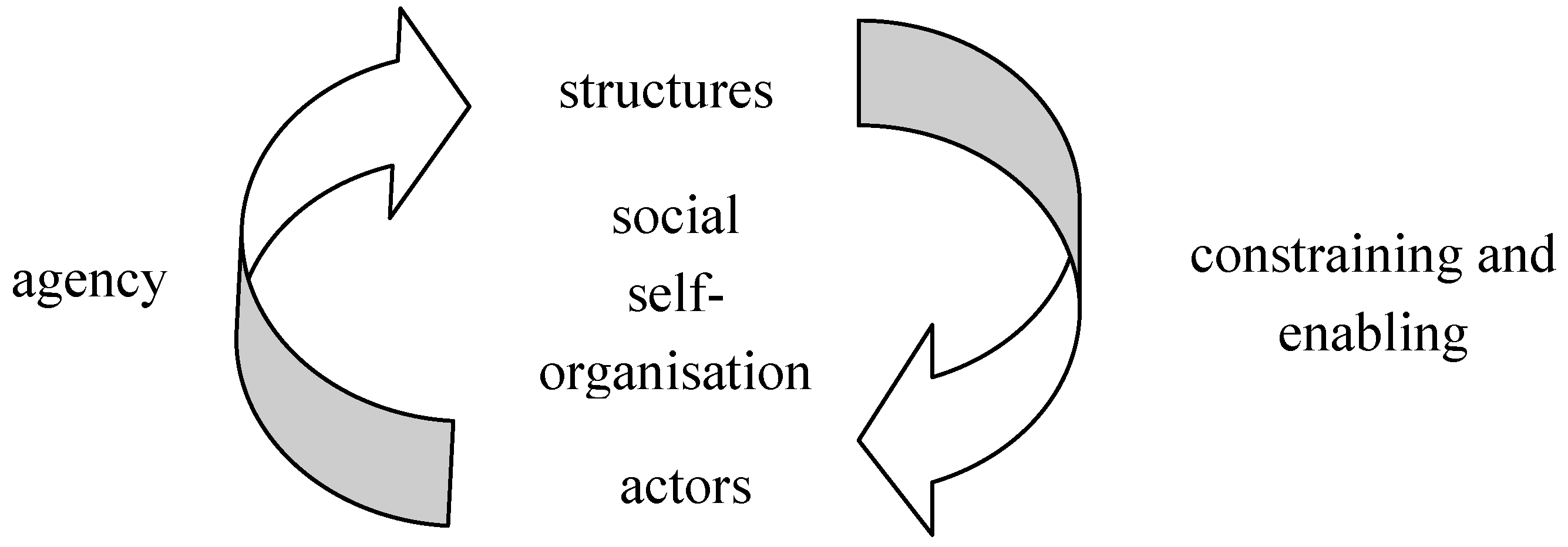

This problem can be solved dialectically: Marx wrote [

30: p. 8]: “In the social production of their existence, men inevitably enter into definite relations, which are independent of their will“. For economic relationships, this is surely true. But there are also social relationships such as cultural ones where humans often can choose whether they want to enter them or not. For example I can not choose if I want to enter a labour relationship because I have to earn a living, but I can choose which political party I want to belong to and which cultural relationships I want to enter. So one can say that concerning the total of society, individuals enter social relationships that are mostly independent and partly dependent on their will. In a social relationship, a human being refers in his actions to other humans or groups and the latter refer in subsequent actions to the first actions in a feedback-process. By social actions, social structures are constituted and differentiated. The structure of society or a social system is made up by the total of normative behaviour – it includes (as we will see) social forces and social relationships. By social interaction, new qualities and structures can emerge that cannot be reduced to the individual level. This is a process of bottom-up emergence that is called agency. Emergence in this context means the appearance of at least one new systemic quality that cannot be reduced to the elements of the systems. So this quality is irreducible and it is also to a certain extent unpredictable, i.e. time, form and result of the process of emergence cannot be fully forecasted by taking a look at the elements and their interactions. Social structures also influence individual actions and thinking. They constrain and enable actions. This is a process of top-down emergence where new individual and group properties can emerge. The whole cycle is the basic process of systemic social self-organisation that can also be called re-creation because by permanent processes of agency and constraining/enabling (structuring) a social system can maintain and reproduce itself (see

fig. 1). It again and again creates its own unity and functioning.

Such a dialectic had already been anticipated by Karl Marx: “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past” [

27: p. 115]. On the one hand he refers to structures that influence actions by saying that there are already existing and given circumstances, on the other he stresses the role of individual and group actions that create a historical development of society. At another instance Marx mentioned similarly that “

just as society itself produces

man as man, so is society

produced by him“ [

26: p. 537].

Jean-Paul Sartre argued in favour of full freedom of action in his early works such as “Being and Nothingness” [

33]; and so he left out the constraining role of social structures. In his late works he spoke of a dialectic of facticity and freedom [

34]: E.g. he mentions that the revolutionary individual is a free, accidental being that is tied up in and imprinted by existing society and history (facticity) and that this individual is nonetheless able to go beyond existing society and to change it (freedom). So old Sartre also saw the dialectic of structures and actions.

In contemporary sociology such a dialectical causality has become more and more important. For example Anthony Giddens [

18] argues in his theory of structuration that social structures are medium as well as outcome of social actions (for a discussion of the relationship of Giddens’ theory of structuration and social self-organisation see [

14]]). Similar arguments can be found in the works of Pierre Bourdieu (for a discussion of Bourdieu’s works in the context of social self-organisation see [

15]). Habitus as the specific ways of thinking and acting of social groups is an aspect of social actions. Bourdieu [

4] says that habitus is a structured and structuring structure. It is being structured by the conditions of existence that can be described by the distribution of capital in society. Bourdieu distinguishes three types of capital: economic capital (commodities, money capital), social capital (social relationships and origin) and cultural capital (level of education, qualification, knowledge). Habitus on the other hand also structures social practices, tastes and life styles. Life styles and practices are again closely related to social structures and so Bourdieu also conceives the relationship of structures and actions as a dialectical one.

Figure 1.

Self-organisation in social systems.

Figure 1.

Self-organisation in social systems.

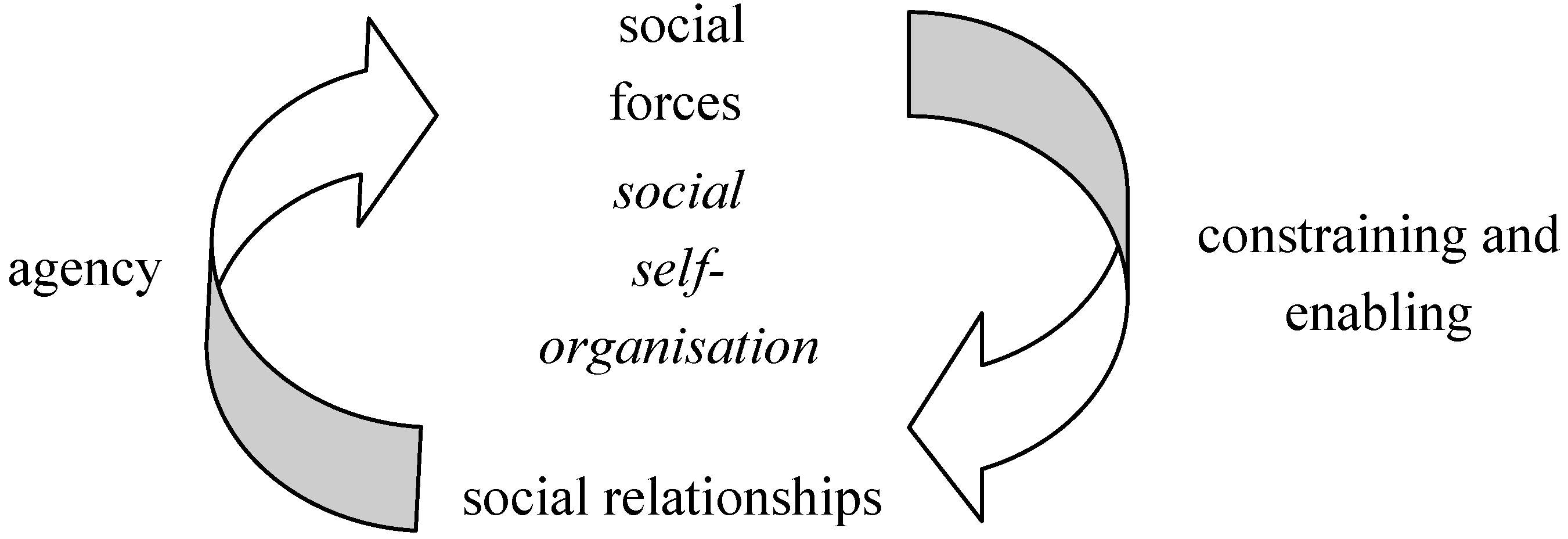

On the structural level of society, we find social forces and social relationships. Social forces are entities that enable social organisation and are developed by human beings entering social relationship. Social forces are modes that co-ordinate, orient, guide, enable and constrain social actions and relationships. They are medium and outcome of social actions. In society we find economic (productive), political and cultural forces. And there are different social relationships – economical, political and cultural ones – that individuals enter which are mostly independent and party dependent from their will.

In re-creation of society and social systems, we also find a dialectic of social forces and social relationships on the structural level: Based on social forces, individuals enter social relationships which are already a structural aspect of society. Agency within these relationships results in structural forces that again influence social relationships. Within these social relationships, individual actions and thinking are imprinted, constricted and enabled by the structural forces. So the process of structuring influences social relationships in a first step and the individual in a second step. The re-creation of society involves a dialectic of structures and actions as well as a dialectic of social forces and social relationships.

Terming the self-organisation of society re-creation acknowledges as outlined by Giddens the importance of the human being as a reasonable and knowledgeable actor in social theory. Giddens himself has stressed that the duality of structure has to do with re-creation: “Human social activities, like some self-reproducing items in nature, are recursive. That is to say, they are not brought into being by social actors but continually

recreated by them via the very means whereby they express themselves as actors“ [

18: p. 2]. Saying that society is a re-creative or self-organising system the way we do corresponds to Giddens’ notion of the duality of structure because the structural properties of social systems are both medium and outcome of the practices they recursively organise and both enable and constrain actions. “According to the notion of the duality of structure, the structural properties of social systems are both medium and outcome of the practices they recursively organise” [

18: p. 25] and they both enable and constrain actions (p. 26). Social systems and their reproduction involve conscious, creative, intentional, planned activities as well as unconscious, unintentional and unplanned consequences of activities. Both together are aspects, conditions as well as outcomes of the overall re-creation/self-reproduction of social systems. Social structures don’t exist external to or outside of human behaviour and relationships, they are constituted within and through social actions. Social forces are themselves social relationships, but they are distinguished social relationships that form the foundation of a specific social subsystem and constitute the driving force of this subsystem. E.g. politics in modern society has to do with many aspects such as regulation, laws, policies, the state, non-government-organisations etc., but the driving force of politics is power that is itself a social relationship.

The mutual relationship of actions and structures is mediated by the habitus, a category that describes the totality of behaviour and thoughts of a social group. The habitus is neither a pure objective, nor a pure subjective structure. The habitus means

invention [

3: p 95,

6: p. 55]. In society, creativity and invention always have to do with relative chance and incomplete determinism. Social practices, interactions and relationships are very complex. The complex group behaviour of human beings is another reason why there is a degree of uncertainty of human behaviour [

3: p. 9,

5: p. 8]. Habitus

both enables the creativity of actors and constrains ways of acting. The habitus gives orientations and limits [

3: p. 95], it neither results in unpredictable novelty nor in a simple mechanical reproduction of initial conditionings [

3: p. 95]. The habitus provides conditioned and conditional freedom [

3: p. 95], i.e. it is a condition for freedom, but it also conditions and limits full freedom of action. This is equal to saying that structures are medium and outcome of social actions. Very much like Giddens, Pierre Bourdieu suggests a mutual relationship of structures and actions as the core feature of social systems. The habitus is a property “for which and through which there is a social world” [

6: p. 140)] This formulation is similar to saying that habitus is medium and outcome of the social world. The habitus has to do with social practices, it not only constrains practices, it is also a result of the creative relationships of human beings. This means that the habitus is both opus operatum (result of practices) and modus operandi (mode of practices) [

3: pp. 18, 72ff;

6: p, 52].

Figure 2.

The dialectical relationship of social relationships and social forces.

Figure 2.

The dialectical relationship of social relationships and social forces.

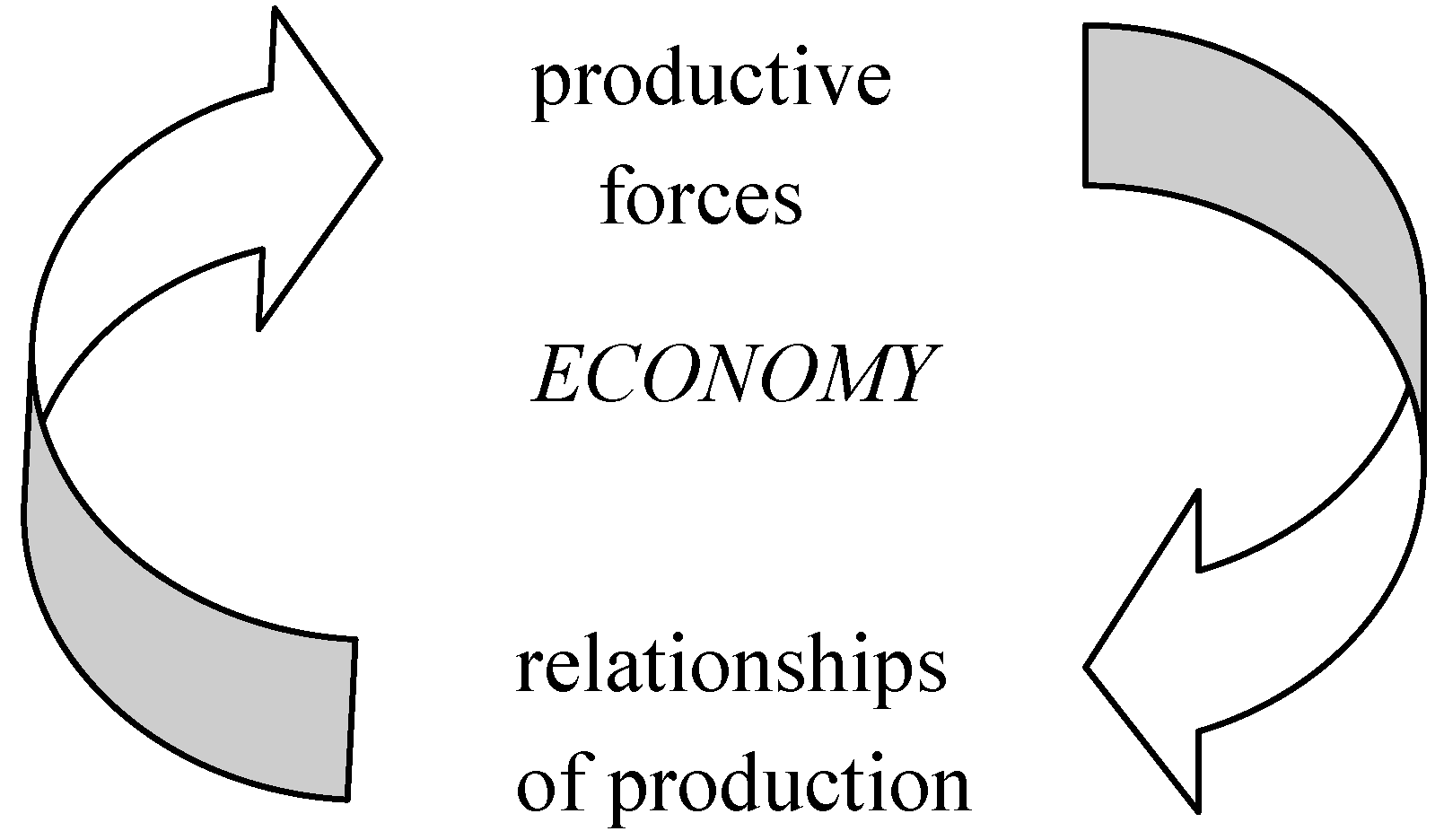

Economic relationships are also called relationships of production. These are economically mediated relationships that are oriented on production and reproduction. In modern society, these relationships are class and market relationships. A class relationship is a social relationship that involves the domination and exploitation of one group by another one. Exploitation can be defined as the transfer of quanta of living labour from a controlled and exploited group to a controlling and exploiting group that can make use of an asymmetrical distribution of power and means of coercion. Relationships of production are social relationships oriented on production and the co-action of labour forces and means of production. They include relationships of property, distribution and labour. In modern society, capital, wage labour, commodities, markets, classes and exchange value are basic economic relationships.

Relationships of productions are based on productive forces and as a result of them the productive forces are developed. Productive forces can be seen as a system of living labour force and factors that influence labour. Living labour and its factors form a relationship that changes historically and is dependent on a concrete formation of society (such as capitalism). The influencing factors can be – as suggested by Marx – summed up as subjective ones (physical ability, qualification, knowledge, abilities, experience), objective ones (technology, science, amount and efficacy of the means of production, co-operation, means of production, forms of the division of labour, methods of organisation) and natural ones. These forces can only be viewed in their relationship to living labour. The system of productive forces can never be reduced to these forces, the system is only possible in combination with human labour. This system is more than the sum of its parts, it is an integrated whole that lies at the foundation of economic processes. In relationships of production it is determined how productive forces such as the means of production are constituted, distributed, disposed and possessed.

Figure 3.

The re-creation of the economy.

Figure 3.

The re-creation of the economy.

Economic forces influence, constrain and enable individual actions and the relationships of production. So we find a double economic process of agency and structuring that constitutes the basic cycle of self-organisation/re-creation which is typical for the economy. Economic processes have to do with the production, distribution and consumption of use values and resources. In the process of production members of society appropriate natural products for creating articles corresponding to human requirements, in distribution the products are allocated the share the individual receives of these products is determined, in consumption the products become objects of use, they are appropriated by individuals and become the direct object and servant of an individual need, which its use satisfies [

28: p. 620]. “Production, distribution, exchange and consumption thus form a proper syllogism; production represents the general, distribution and exchange the particular, and consumption the individual case which sums up the whole“ [

28: p. 621].

On the political level, we find political relationships that individuals enter based on political forces. In modern societies these are political groups (political parties and political organisations in civil society) and relationships between these groups that follow organised procedures (political discourse, elections, protests, parliamentary discussions etc.). By such relationships, a specific disposition of political power is formed and political conflicts may arise. This results in the emergence and differentiation of political forces. The important political force is power. Power can be defined as the disposition over the means required to influence processes and decisions in one’s own interest, domination refers to the disposition over the means of coercion required to influence others or processes and decisions. Domination always includes sanctions, repression, threats of violence and an asymmetric distribution of power. In political relationships it is determined how power is constituted, distributed, allocated and disposed. Political forces are the foundation for political relationships and they are differentiated and developed by political relationships. In modern society, basic political relationships are laws and the state. They influence individual actions/thinking and political forces. Political re-creation is a double process of agency (decision procedures) and enabling/constraining. This is the basic cycle of political re-creation/self-organisation (

fig. 4). In relation to available power resources, decisions are being reached in politics, in order to organise the functioning of society.

The state not only includes the coercive apparatus of political society, but also civil society, i.e. the political non-government institutions [

20: p. 262f]. This means that in modern society political relationships also include market rules, money relationships, financial networks, welfare, associations, trade unions, the political system, think tanks, police, military, secret service, the juridical system, parties, social movements, federations, consultants, monetary and credit relationships, the institutional relationships of capital and labour (as e.g. in social partnerships), forms of state intervention and international regulatory instances.

Figure 4.

The re-creation of politics.

Figure 4.

The re-creation of politics.

On the cultural level, we find cultural relationships that individuals enter based on cultural forces. Cultural relationships are different life styles and interest groups and relationships between these entities. Cultural relationships result in institutions of religion, science, education, art, media, law, privacy etc. and relationships between such institutions. Institutions are modes of social existence that have common goals and rules, define membership and include practices that have a larger temporal and spatial extent. Cultural relationships are based on and result in the differentiation of cultural forces which are socially established and accepted norms and values as well as social knowledge. These cultural forces again influence (enable and constrain) individual and group actions as well as cultural relationships. So we find a double process of cultural agency and enabling/constraining that constitutes the basic cycle of cultural re-creation/self-organisation. In cultural relationships, it is determined how the cultural forces are constituted, distributed, allocated and disposed.

Figure 5.

The re-creation of culture.

Figure 5.

The re-creation of culture.

Culture is not a part of politics, it is a relatively independent subsystem of society that depends on its own logic although it is mutually connected to politics and the economy. In modern society, culture produces hegemony, ideologies and dominating norms and values and results in the accumulation of cultural capital within the framework of cultural forms (dominating norms, knowledge, values, ideologies) and cultural relationships.

Hegemony can be seen in accordance with Antonio Gramsci as “the ‘spontaneous’ consent of the masses who must ‘live’ those directives [of the state, CF], modifying their own habits, their own will, their own convictions to conform with those directives and with the objectives which they propose to achieve” [

20: p. 266]. Hegemony can only work in and with ideology. An ideology is a system of ideas and believes that dominates the consciousness of a human being or a social group [

1]. This definition shows that ideologies are cultural aspects of societies that are based on the principle of domination, they fulfil a certain function. Ideology is a 'representation' of the imaginary relationship of individuals to their real conditions of existence, i.e. they do not map reality, but are social constructions that show how certain groups want to define reality in order to make others see reality the same way. Someone who favours a certain ideology takes part in certain practices (going to church, meetings, consumption of information and culture etc.). These practices show that ideologies have a material existence and are not confined to the ideational realm. Ideology calls human beings as subjects, this is a process termed “interpellation” by Louis Althusser. Ideology interpellates individuals as subjects and makes them become subjects (members of families, churches, associations, parties etc.). An interpellation takes place in the name of an absolute subject (god, leader, state, boss, guru etc.). The individual is interpellated as a free subject so that it voluntarily submits to the will of the absolute subject.

4. The Individual and the Information Process in Social Systems

An individual has a specific psychological structure of thinking which is influenced by social forms and by the social relationships it enters and by which it influences processes of agency. In social systems individual values, norms, conclusions, rules, opinions, ideas, and believes can be seen as individual information. Why do we speak of individual information although it is clear that an individual is always a social being? Each individual is a unique character that has a specific cognitive structure. Individual information refers to the individual as a living and psychological system. Individuals are the components of social systems, individual information describes aspects of information generation within these moments. This process is always influenced by society and the social relationships the individual enters, but it is never determined by them. So e.g. we find socially accepted norms, rules and values in society which influence individual thinking and actions to a certain degree. But it cannot be concluded that all individuals necessarily share these social norms and rules because they are creative and self-conscious beings that have a certain degree of freedom of action and thinking. The extent of this degree depends on the degree of participation and democracy of the existing social structures and actions. Social and individual norms, values and rules cannot simply be mapped linearly, there is a complex relationship between individual thought and social conditions. This complexity also speaks in favour of the term individual information because it takes into account that individuals have unique and complex cognitive structures.

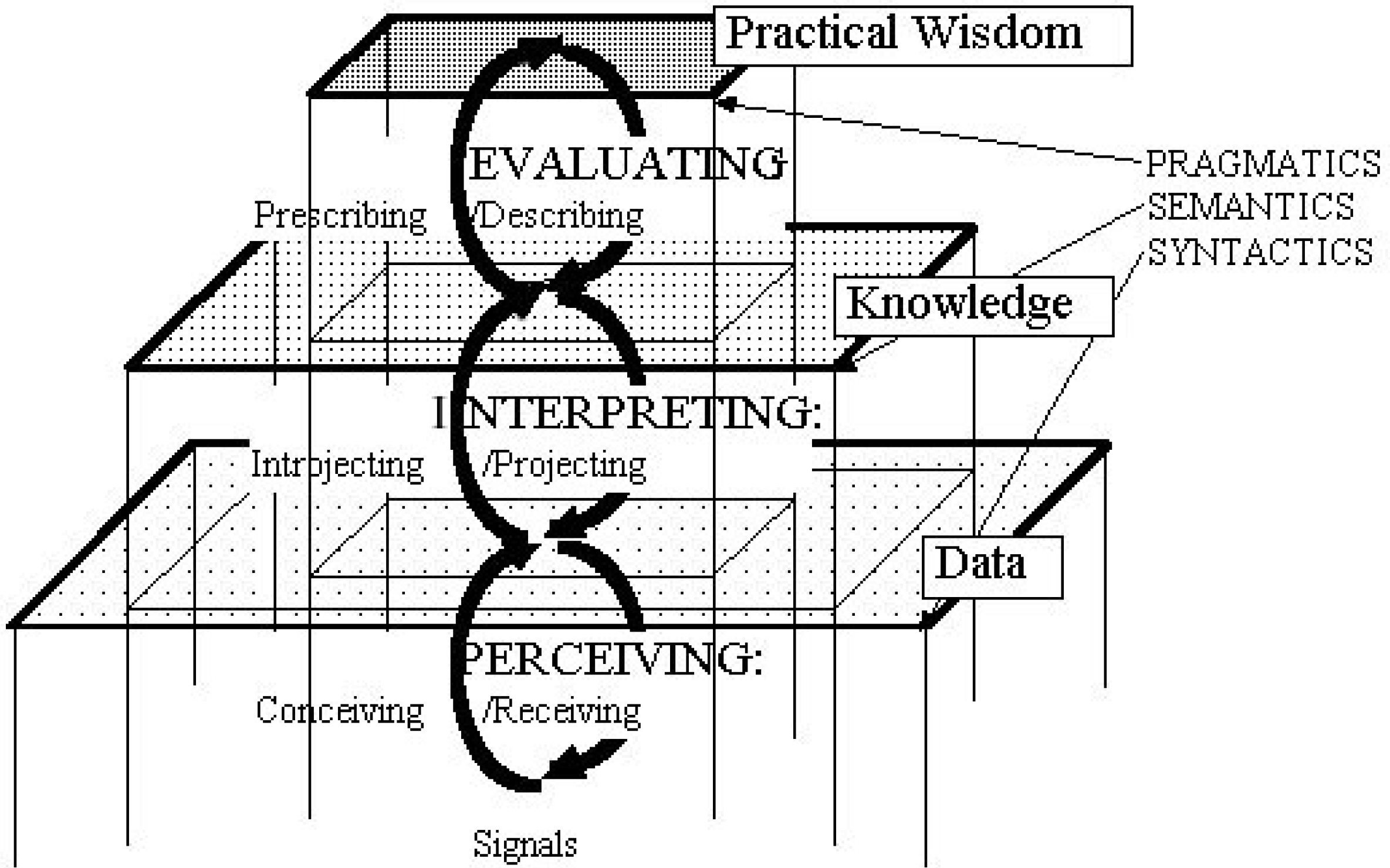

A sign can be seen as the product of an information process. An information process occurs whenever a system organises itself, that is, whenever a novel system emerges or a qualitative novelty emerges in the structure, state, or behaviour of a given system. In such a case information is produced. It is embodied in the system and it may then be called a sign. We also find different processes of self-organisation within the human mind and body. This results in the emergence of individual information. In the constitution and differentiation of individual information the signs data, knowledge, and individual wisdom can be identified (

fig. 6; see also [

16], [

22], [

23]).

Cognition is always bound up with the outside world, a subject relates itself to events and states of its environment. The informational happening can be described as layered; levels of higher and lower quality can be distinguished. A transformation of information from lower to higher levels takes place. The generation of individual information starts with the reception of signals from the environment. The update of the signals starts with a particular state of experience of the cognitive system. Receiving applies to the uptake of signals that come from the perceivable environment. Conceiving is dedicated to the registration and bringing together of the signals to a “view” of some aspects of the environment. Perception unites conception and reception: it is an unceasing movement, an oscillation between reception and conception. An act of perception involves the reception of signals and the conception of impressions, i.e. a new whole that is called data. Perception is a process that reflects and potentially changes the current cognitive structure. The emerging structure is the starting point of the next perception. The whole can acquire a new emerging quality that the previous one did not have. Thus, on the first level, signals are made into data by perception, an act that involves reception and conception.

On the next level, the data is interpreted; meaning is given to the data. Thus knowledge is formed. The process of interpretation involves the interplay of projection and introjection. It starts with a certain state of interpretation/knowledge, which is the basis for the emergence of new knowledge. Projection means that first the system projects its cognitive structures onto reality, i.e. the current state of knowledge is applied to the data. Introjection means that the data can be interpreted in such a way that the structure of knowledge changes–new knowledge emerges. The system has introjected reality into its structure. New areas of reality, new experiences have been brought into the system. As on the first level reception and conception, there are two opposing processes: projection and introjection. They form part of the motor of the endless movement of cognition.

On the third level, knowledge is evaluated and sense is made of it. Individual information such as values, norms, rules, opinions, ideas, and believes is created by the fact that the subject puts its knowledge into the context of its goals. This action is seen as evaluation, which is made up of the elements of description and prescription. The process starts with the current state of individual information in a particular situation where an individual must act in order to solve a problem. Description means that on the basis of the current individual information structure the individual is looking for solutions. The situation and the solutions refer to the knowledge at the lower level, which represents facts and laws. In the prescriptive phase a decision is made about the implementation of a solution. A solution considered good, beautiful, and just is selected. At this upper level the process of cognition cumulates to practical wisdom which is seen as individual information that allows an individual to create situations that he/she experiences as good, beautiful, and just. The existence of individual wisdom does not necessarily mean that the decisions taken by individuals are socially wise ones.

The semiotic triad of syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic aspects of signs can be mapped to these three levels of individual information.

Figure 6.

The Generation and Differentiation of Individual Information.

Figure 6.

The Generation and Differentiation of Individual Information.

Information has subjective as well as objective aspects. It is on the one hand a property and product of cognitive systems, a difference that makes a difference, and as such it is selected in the communicative process that can be considered as Niklas Luhmann [

24] has shown as an emergent synthesis of three selections (selection of information, uttering and understanding). Due to the selectivity of the communication process, information has a certain degree of uncertainty. On the other hand information is also an objective, reflective social relationship: If actors communicate, information exists as an objective relationship between them and this relationship involves reflection. Reflection (Widerspiegelung) doesn’t mean the mechanical reproduction of data by a receiver, it only means that in the case of communication there is a reaction of one communication partner to the symbolic actions of the other partner. It is determined that he reacts and in this reactions he makes uses of symbols, otherwise one couldn’t speak of communication. But it is not determined how he reacts exactly, this is relatively open, but frequently also to a certain extent predictable due to certain regularities and standardised modes of behaviour that can be found in the social world. Such reflective reactions are neither completely determined, nor completely indetermined, their causality can be characterised as relative chance and incomplete determinism. Such objective information relationships occur milliards of times per day relatively stable, hence information as a social relationship is relatively probable. However there are degrees of uncertainty due to different dispositions, norms, values, habitus, cultural contexts, interpretative schemes, tastes, life-styles etc. of the partners in a communicative setting. Structures are totalities of durable and institutionalised behaviour. They can be found in all subsystems of society. Structures mediate communications and actions, they are medium and outcome of actions and communications. Structures are social relationships and a type of information in society. Social information is a communicative relationship between actors where artefacts are included in order to produce sense and achieve goals. Knowledge as an organised form of data that are interpreted, assessed and compared, is contained in social artefacts. Artefacts store dead labour and knowledge of society. Social structures are media of society because they mediate social actions and communications. They store and fix knowledge and hence they simplify actions and communications because the foundations of these processes don’t have to be produced permanently, they can be achieved by making use of structures. Hence by storing knowledge, social structures reduce social complexity. Structures are carriers of knowledge, they are the foundation of temporal and spatial extension of social systems. Social structures make possible a continuity of social reproduction across space and time, they result in the temporal and spatial distanciation of social relationships without the loss of continuity. Structures also produce specific forms of contiguousness and hence they dissolve distances by reembedding social relationships that are disembedded in space-time. Social structures are a foundation of action and communication, they enable a certain degree of mobility, they mediate, organise, and co-ordinate social relationships and communications.

Anthony Giddens argues that there are storage capacities in society which enable the existence of institutional forms which persists across generations and shape past experiences that date back well beyond the life of any particular individual ([

17: pp. 35, 39, 94f, 144, 157-181]; [

18: pp. 180-185]; [

19: pp. 13f, 172-197). Allocative and authorative resources can be stored across time-space distances. Storage of authorative resources involves the retention and control of knowledge. In non-literate societies the only “container” storing knowledge were human memory, tradition and myths. Writing and notation have allowed a certain time-space distanciation of social relationships. Other forms of storing that have followed and have caused further time-space distanciation are cities, lists, time-tables, money, money capital, nation-states, communication and transportation technologies in general and especially the rapid-transit transportation and electronic communication technologies (including electromagnetic telegraph, telephone and computer mediated communication).

Also the brain contains and stores knowledge, communication means a comparison of knowledge, norms, values, ideas etc. Knowledge of actors is contained in the social relationships they enter. Communication means information production, but this information can be assessed as being useful or not. By the mutual mediation of knowledge, new knowledge can emerge in a creative process. Social information relationships contain permanent flows of knowledge between actors, these flows can become productive. Such a production process results in the differentiation of the cognitive knowledge structures of the involved actors. Each day we enter multiple information relationships that don’t effect our knowledge, but other experiences, relationships and communications change our knowledge, views, norms, values, interpretative schemes etc. In such a case, knowledge flows are considered as meaningful, an information relationships gains a productive dimension.

Information exists in all social relationships, but it has different effects. We neither photographically and mechanically map knowledge, nor are we autonomous knowledge producers. Due to certain normative dispositions certain reactions and interpretations to a stimulus are more probable than others. But the human being is a being that can change his views during productive discourses, hence social information relationships not only increase the knowledge of a subject, they also result in a (faster or slower) differentiation of definitions. Human interpretation is neither mechanical mapping, nor coincidental construction, but constructive reflection (konstruktive Widerspiegelung). Reflection involves reaction to external stimuli during the course of communications where different alternative interpretations and behaviours are possible. It depends on the degree of participation and democratisation of society to which extent interpretation and critical reflection are activated.

Information as reflection in physically self-organising, i.e. dissipative systems has a low degree of autonomy, there is a simple reaction to stimuli. In autopoietic, biologically self-organising systems, information production also has to do with interpretation and the selection of certain reaction. Information here not only has syntactic aspects, but also semantic ones and there is a larger degree of freedom than in dissipative systems. The evolutionary systems with the highest degree of freedom are socio-culturally self-organising, i.e. auto- and re-creative systems. Here the ability of creating new realities and environments is important, information is produced as a reaction to stimuli, there are certain interpretations and based on these foundations practical actions and communications are selected. In social systems, information has practical effects onto the environment, it involves creativity, norms, values and the selection of behaviours and communications. These are aspects of pragmatics, pragmatics is an aspect of social information that distinguished it from physcial and biological information.

Social structures store information about society. Hence there are also certain categories that can be termed social information. In re-creative, i.e. social systems, self-organisation produces what can be termed social information: The word "social" in the term social information denotes that such a form of information is constituted in the course of social relationships of several individuals. According to Max Weber a social relationship is established if an interrelated reference exists between two actors. Social acting is orientated on meaningful actions of other actors. Social actions are a necessary condition of a social relationship, but not a sufficient one because social acting doesn't necessarily require the actors to mutually refer to each others actions: One actor can refer to the actions of another without the latter referring to those of the first.

We consider the scientific-technological infrastructure, the system of life-support elements in the natural environment and all else that makes sense in a society, i.e. economic property, political decision power, and the body of cultural knowledge, norms and values to be social information. Within the core of a social system and of society, there are three manifestations of information: property, decision power and definitions. They store information about past social actions and simplify future social situations because by referring to social information the basics of acting socially do not have to be formed in each such situation. Social information can be seen as a durable foundation of social actions that nonetheless changes dynamically.

The three basic cycles of self-organisation/re-creation we have lined out, all result in the bottom-up emergence of social information and the top-down emergence of individual information. In the economic cycle, social information emerges as dispositions (economic information), in the political cycle as decision power (political information) and in the cultural cycle as definitions (cultural information). These types of social information influence individual actions and thinking and hence individual information. So the dialectic of structure and action that lies at the heart of social self-organisation/re-creation can on the informational level also be described as a dialectic of individual and social information: A social system organises itself permanently in order to maintain itself and it permanently produces and changes social information. As shown in

figure 7 this is a dialectical process: Social information emerges from individual information. The subjects of society create and change social systems by relating their actions and hence their consciousness. New patterns emerge from this process. On the other hand we have a process of dominance: Individual consciousness can only exist on the foundation of social processes and social information. Social information restricts and enables individual consciousness and action. In this dialectical relationship of individual and social information, we have the bottom-up-emergence of social information and the top-down-emergence of individual information. On the macroscopic level of the social system, new social information can emerge during the permanent self-organisation/re-creation of the system. On the microscopic level, social information makes an effect in a process of domination and new individual information can emerge. So domination can be seen as a type of top-down-emergence. The endless movement of individual and social information, i.e. the permanent emergence of new information in the system, is a two-fold dialectical process of self-organisation that makes it possible for a social system to maintain and reproduce itself.

Figure 7.

The informational level of the re-creation of social systems.

Figure 7.

The informational level of the re-creation of social systems.

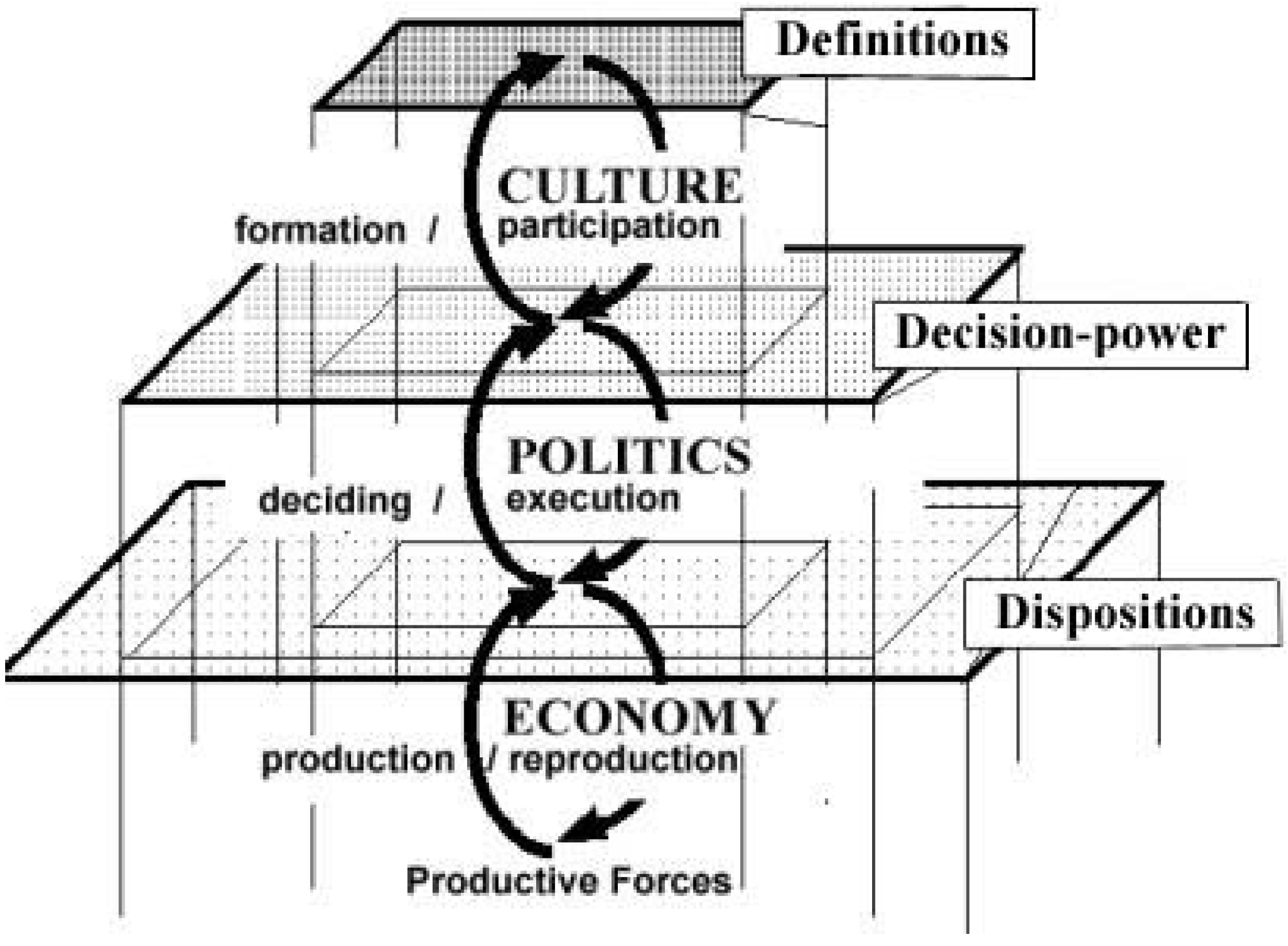

The three basic cycles of social self-organisation that we have lined out can also be summed up to a general model of systemic social self-organisation (see [

13], [

16]): The economy as the base of society makes use of productive forces in order to establish a double process of production and reproduction that results in the emergence of economic dispositions (economic information). This is the foundation for the political cycle of self-organisation that consists of a double process of deciding and executing which results in the emergence of decision power (political information). These decisions concern the use and distribution of social resources. Politics is the foundation for the cultural cycle of self-organisation that consists of a double process of formation and participation that results in the emergence of social norms, values and knowledge (definitions). Such a model describes the re-creation of society or of a social system as a whole (see

fig. 8, for detailed descriptions see [

13], [

16]). It is hierarchical and layered and involves three processes of bottom-up-emergence and three processes of top-down emergence. Society is not considered as mechanistic, but as a complex system by describing its reproduction with the help of cycles of self-organisation that operate by a mutual and multidimensional type of causality.

Figure 8.

The re-creation of society as a whole.

Figure 8.

The re-creation of society as a whole.

When two systems interact, they enter an objective relationship, i.e. a (mutual) causal relationship is established. A portion of subjective, systemic information (“cognition”) is communicated from system A to system B (and vice versa, “communication”). This causes structural changes in the other system. If there is an information relationship between the two systems, it is determined that there will be causal interactions and structural effects. The structure of the systems (structural, subjective information) changes, but we don’t know to which extent this will actually be the case, which new subjective information will emerge, which information (structures) will be changed etc. There are degrees of autonomy and freedom (=chance). If structural changes in system B take place and are initiated by system A, this means an objectification of subjective information of A in B from the point of view of A. From the point of view of B it means subjectification of objective information from the environment. In a communication process, this also takes place the other way round. By communication it can not only be the case that an objectification of information in some of the involved systems takes place, it can also be the case that due to the synergies between the systems new qualities (information) emerge in their shared environment (“co-operation”). Structural, subjective information of the involved systems is co-ordinated, synergies arise and hence something new is produced commonly in a self-organisation process. The new structure or system that arises is an objectification of subjective information of the involved systems. Information in self-organising systems has cognitive (subjective), communicative (new subjective information (=structures) emerges in systems due to interaction) and co-operative aspects (interaction results in synergies that cause the emergence of new, objectified information in the shared environment of the involved systems). Information has both objective and subjective aspects.

5. Conclusion

This paper has shown that the individual plays an important role in the re-creation of society. Society can only reproduce itself when individuals enter social relationships that result in the emergence and differentiation of social forms and social information. These structural categories influence individual actions, information and thinking. This dialectical process of actors and structures lies at the heart of social re-creation. Without the individual as a creative, social being, re-creation of society would not be possible.

We have not covered here aspects of how social relationships and structures look like today. In modern society they are imprinted by social antagonisms. Social relationships today are mainly shaped by competition, domination, exclusion and the asymmetrical distribution of power. There is a lack of subjective self-organisation in the sense of self-determination, participation and direct democracy (see [

11]). This results in conflicting social situations on the economical, the political and the cultural level and antagonistic economic, political and cultural structures and forms. These antagonistic social relationships and forms result in a crisis-ridden evolution of modern society that has culminated in the emergence of global problems that threaten the existence of humankind (see [

12]). For solving these problems and ensuring a sustainable development, the existing antagonistic social information and relationships would have to be sublated so that a new harmonious type of systemic social re-creation/self-organisation could emerge.

Marx has shown that the analysis of the individual must be one of its historical and present conditions of life. So e.g. in the German Ideology and the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts which are important works for the Marxist concept of the individual, Marx speaks on the one hand generally about the individual (as a producing, social being etc.), and on the other hand takes a look at the qualitative moments of society that at present influence the life of the individuals. In this analysis the concept of the alienation of the individual in modern society is important. So Marx on the one hand is interested in the general reproduction of society, on the other he describes the capitalist mode of reproduction is one that is based on alienation, exploitation, heteronomy and a lack of self-determination of the human being.

Marx points out that with the division of labour a contradiction between the interest of the separate individual and the communal interest of all individuals who have intercourse with one another emerged. As long activity is not voluntarily, but naturally, divided, man's own deed would become an alien power opposed to him, which enslaves him instead of being controlled by him ([